Kurds are a strategic ally for the US

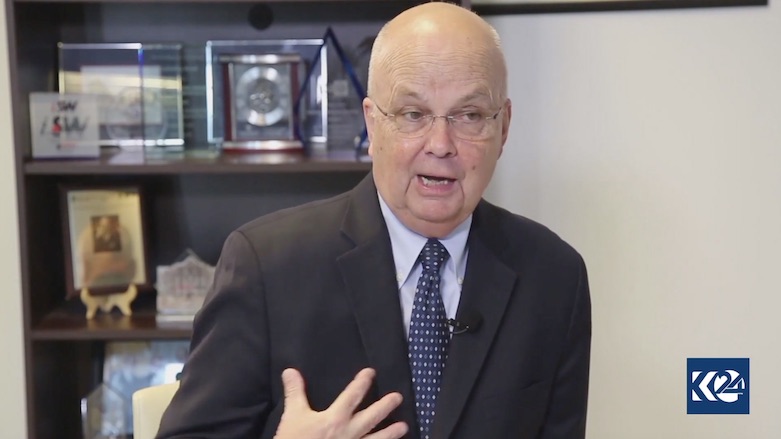

Kurdistan 24 spoke at length with Gen. Michael Hayden, former Director of the CIA and NSA, last Friday about his new book, The Assault on Intelligence, and its implications for contemporary events. This was Part I of the interview; below is Part II.

WASHINGTON DC (Kurdistan 24) – “Absolutely,” the Kurds are a strategic ally, Gen. Michael Hayden told Kurdistan 24. If one thinks in terms of the region, “the Kurds have been America’s best friends for decades now.”

“In this last crisis” against the Islamic State (IS), “the Kurds had a virtue that not many people had: they stood up and they fought,” Hayden continued.

“I do think there is a certain sense of indebtedness we have to the Kurdish people,” he affirmed.

Hayden, who was appointed NSA Director under Bill Clinton and then became CIA Director under George W. Bush, explained that the “post-World War I state structure in the Middle East is gone.”

“And it’s not coming back,” he continued, at least not “in its previous form, where countries like Iraq and Syria were unitary states.”

That is Hayden’s firm and fixed point of departure from much of the thinking in Washington on this problem.

Typically, as he noted, people believe the way to “fix” a problem is to restore the status quo ante—an apt description of US policy, at least so far, toward post-IS Iraq and Syria.

But, as Hayden explained, his book, The Assault on Intelligence, suggests that the changes that have occurred in the region “have been so fundamental that the status quo ante will not be stable.”

Therefore, “we need to be creative going forward.”

Above all, Hayden proposes that the political entities of the region should be aligned with the political communities. One might think that is not so radical an idea, but few others have embraced it—which may also help explain why, despite fifteen years of engagement in Iraq, the US still faces very considerable challenges.

Hayden sees four such entities in the areas we call Iraq and Syria. One is Kurdistan, encompassing both the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Syrian Kurdistan as well.

A second is the “rump state” of Syria—the area controlled by Bashar al-Assad and his regime, which Hayden refers to as “Alawistan.”

A third area is Iraq, “with a predominantly Shi’a identity.” It would not be “an Iranian satellite,” in Hayden’s view, given the significant differences between the two: Arabs vs. Persians, Karbala and Najaf vs. Qom, etc.

What is missing is a “Sunnistan”—a stable, Sunni Arab region. “We had a Sunnistan, he says, but “it was governed by [IS.] It was an unacceptable Sunnistan.”

“So can we build a Sunnistan that both we and the Sunnis can live with?,” he asks.

Hayden stresses that he is talking about political “entities,” and “not necessarily countries,” with hard and fast borders, but “entities in which Kurds feel as if they have a good role in governing,” and the same with Sunnis and Shi’ites.

In other words, Hayden is suggesting politics on a western model: the government reflects the basic, most deeply-felt identity of the people.

The boundaries of Iraq and Syria “are western lines,” Hayden notes. They were “artificial” and “kept in place by power,” but “now we need a new formula.”

Hayden also credits Joe Biden, who as a senator, before becoming vice-president, called for what Hayden called the “dissolution” of Iraq (Biden might describe it a bit differently—decentralization, perhaps—and he was joined then by Sen. Sam Brownback, now Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom.)

As Hayden explains, although he disagreed with Biden a decade ago, “events have taken place” and “new realities have been created.”

Hayden believes the administration was correct to advise its “Kurdish friends” (he stresses the word, “friends”) that the independence referendum was “not a good idea at this time.”

But he also believes that the US should have “a broader view.” Above all, he suggests that the US should begin a dialogue with Ankara and with Baghdad to ask them, “What do you need to be comfortable with a far more autonomous Kurdish region in the heart of the Middle East?”

Underlying Hayden’s thinking is the conclusion that “the old”—i.e. Iraq and Syria—“is gone” and “a successful policy cannot be based simply on going back” to what was.

In his discussion with Kurdistan 24, Hayden also recounted the Bush administration’s attitude toward Turkey and its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“We had some pretty high hopes for President Erdogan,” Hayden said, as he recalled a discussion, in which Condoleezza Rice welcomed Erdogan’s election as Prime Minister.

Stressing that he was summarizing her remarks, rather than repeating them verbatim, Hayden explained that she had said Erdogan represented “a political Islam we can support.” His Justice and Development Party wasn’t Germany’s Christian Democrats, but nonetheless represented “a form of political Islam that was inclusive and progressive,” or so it seemed.

As time passed, however, “the more fundamentalist and autocratic” Erdogan has become, Hayden said. Yet Hayden has warm memories of his many visits to Turkey and “great affection” for the country. So he hopes “we can work our way forward to some kind of better future in our relationship.”

In Syria, Hayden believes the administration “left the field too open” to Assad, Russia, and Iran and that the extent to which Assad has been able to consolidate control has been “a failure of American policy.”

Still, Hayden believes that Syria, like Iraq, will never return to being the “unitary, national state” it once was.

Hayden sees Iran as an aggressive, expansionist state. Tehran now dominates in four Arab capitals: Baghdad, Sana’a, Damascus and Beirut, he explained. He also believes that the Iranian nuclear deal had significant shortcomings.

However, Hayden disagrees with the Trump administration’s decision to leave the agreement. “The word of a country should mean something,” he said. “The Iranians weren’t cheating, and they were further away from a weapon with the deal than they would be without it.”

Rather, Hayden would have preferred the US leave the deal intact and confront Tehran “in a lot of other areas.” Had the administration done so, he suggests, it would have received support from Europe.