Erbil’s Sculpted Testimony: When Public Art Becomes Collective Memory

These statues are far more than ornamentation. They form a grand, open-air gallery—a testament to the indelible imprint of women on Kurdish collective memory.

By Kamaran Aziz

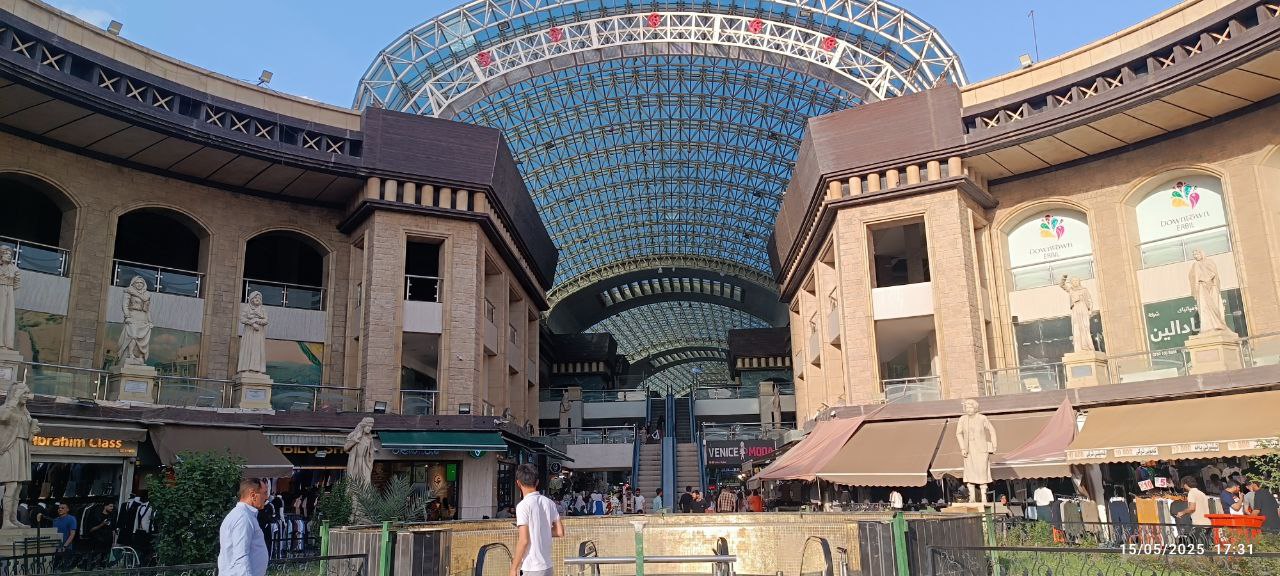

ERBIL (Kurdistan24) – In the heart of Erbil’s lively Downtown marketplace—where vendors call out over fresh produce, the scent of spices perfumes the air, and children weave between stalls—an extraordinary cultural statement quietly commands attention. Nestled amid the commerce and conversation are nearly 120 statues of women: not symbols of myth, but real figures from Kurdish history, immortalized in bronze and stone.

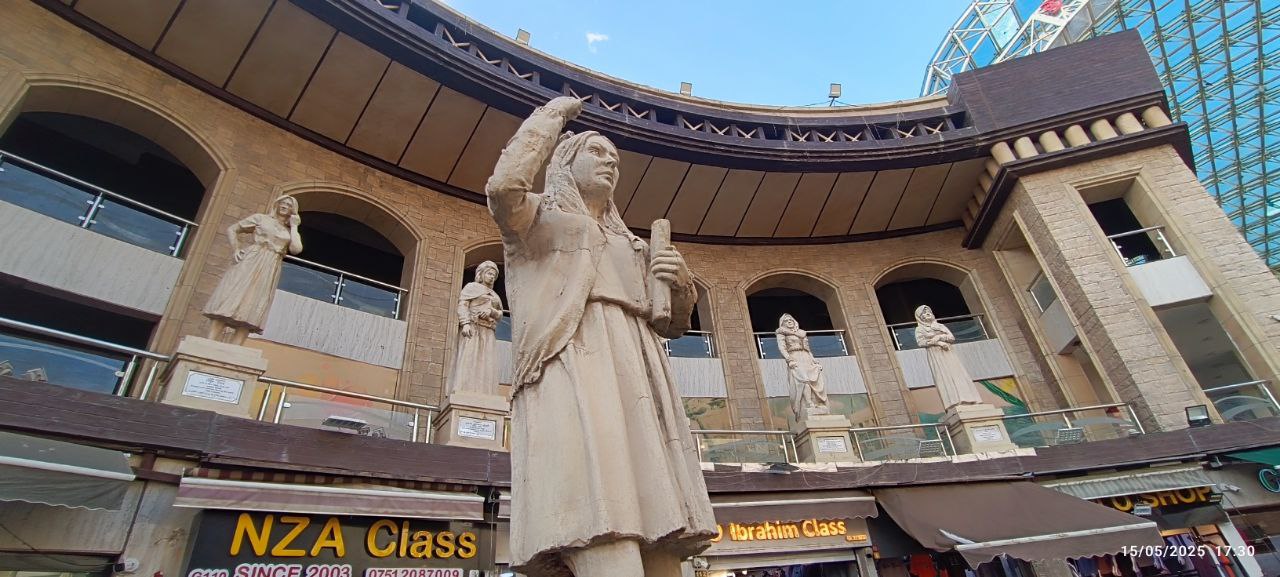

These statues are far more than ornamentation. They form a grand, open-air gallery—a testament to the indelible imprint of women on Kurdish collective memory. Each sculpture offers more than a likeness; it narrates a chapter of resistance, leadership, scholarship, or sacrifice, and reveals the soul of a people who have historically enshrined their reverence for women not only in custom, but in public space.

In a region often clouded by grim headlines about gender inequality, the Erbil marketplace presents a striking and dignified counterpoint. The landscape itself proclaims a truth too often overlooked: that women have stood at the epicenter of Kurdish political, cultural, and intellectual life for centuries.

This cultural inheritance is not merely anecdotal. According to a 2024 report by the European Institute for Studies on the Middle East and North Africa (EISMENA), Kurdish women's activism in Iraqi Kurdistan has long been entwined with nationalist aspirations. Their engagement has evolved from customary familial roles to leading voices in civil society, governance, and protest. The report emphasizes how Kurdish women, even while navigating the constraints of patriarchy, have actively shaped the public sphere through a unique and enduring form of gender-conscious nationalism.

Complementing this analysis, a 2018 academic study by Marlene Schäfers, published in the Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, provides a critical ethnographic perspective on Kurdish women’s pursuit of voice and visibility in male-dominated public discourse. Schäfers explores how Kurdish women have carved out spaces for expression—through song, activism, and political engagement—within the broader struggle for autonomy and dignity.

As one walks into the marketplace, the visual narrative begins.

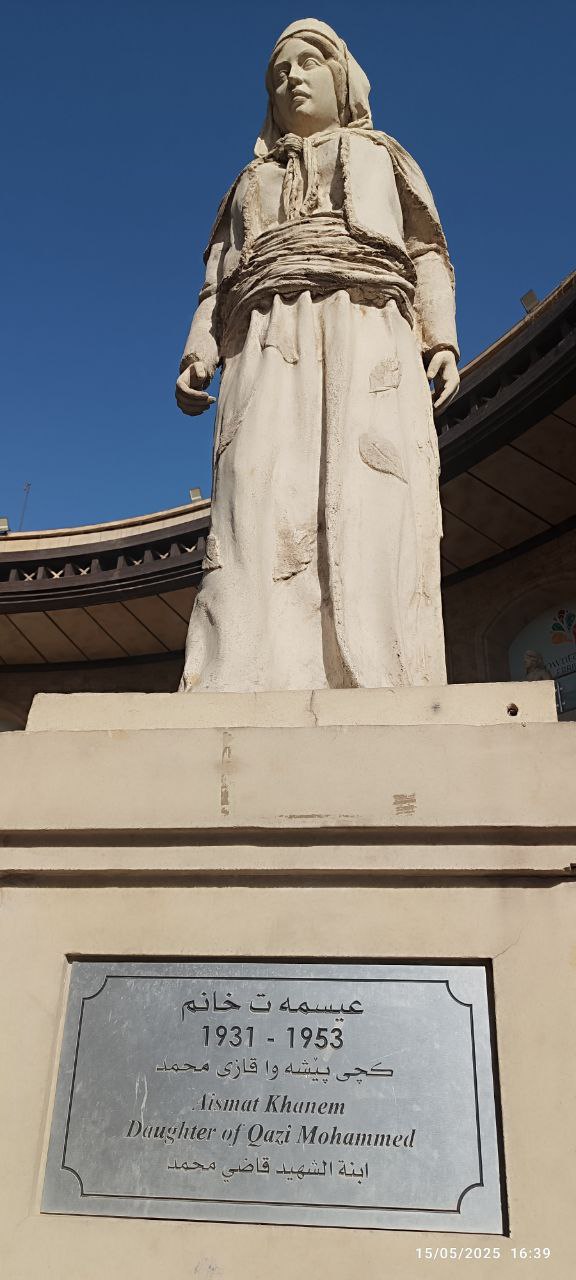

To the right of the gate stands the statue of Aismat Khanem, daughter of Qazi Mohammed, President of the short-lived Kurdistan Republic of Mahabad. Her image recalls a family whose defiance and vision echo still in Kurdish political imagination.

To the left, Salha Khan—the courageous widow of martyred commander Khairullah Abdulkarim—stands in tribute to the quiet, relentless strength of Kurdish women who have shouldered the cost of resistance.

A few steps deeper into the market, the figure of Layla Qasim stands solemnly. Hailing from Khanaqin, Qasim became the first Kurdish woman executed by the Ba’athist regime in 1974 for her political activities. Her legacy is not merely one of martyrdom, but of unwavering defiance in the face of tyranny. Her statue embodies the spirit of countless Kurdish women who have faced repression with courage beyond measure.

Nearby stands Mah Sharaf Khanem Mastoura Ardalan—poet, historian, and intellectual of the 19th century. Ardalan’s literary and historical contributions placed her among the finest minds of her era. Her presence in the market is a reminder that Kurdish women have not only fought on the frontlines of conflict, but have illuminated the pathways of thought, culture, and collective identity.

While Kurdistan, like many societies, still grapples with gender-based violence and degrees of social inequalities, the enduring presence of these statues suggests a deeper, older cultural truth: that the valor, intellect, and sacrifice of women are not exceptions, but foundations. They are not commemorated as anomalies, but honored as architects of Kurdish endurance and imagination.

This phenomenon gains further philosophical depth when viewed through the lens of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s reflections on aesthetics. In his Lectures on Aesthetics, Hegel famously described art as “the sensuous presentation of the Idea,” insisting that sculpture, in particular, serves not merely a decorative function but embodies the spiritual and ethical essence of a people. For Hegel, public artworks such as statues externalize the inner truths and self-understanding of a society. As Hegel states in his Lectures on Aesthetics, "In works of art the nations have deposited their richest inner intuitions and ideas, and art is often the key, and in many nations the sole key, to understanding their philosophy and religion."

In light of this, the statues of Kurdish heroines across Erbil’s marketplace function not merely as historical markers or decorative structures, but as profound vessels of Kurdish spiritual, cultural, and philosophical identity. These monuments carry with them the distilled essence of Kurdish ethical life—its pain, pride, and aspirations—and serve as aesthetic keys to understanding the broader moral and intellectual worldview of Kurdistan itself. As embodiments of the people’s richest intuitions, they offer a window into the consciousness of a society shaped by struggle, endurance, and reverence for its women. In this way, the statues of Kurdish heroines across Erbil’s marketplace function not only as commemorative tokens but as embodiments of the Kurdish spirit—its memory, struggle, and ethical world.

Hegel’s treatment of sculpture within the Classical stage of artistic development reinforces this point. Sculpture, he argues, achieves a rare harmony between form and content, body and soul—an ideal unity embodied in the representation of the human figure. When viewed from this philosophical vantage, the Kurdish marketplace becomes not just a site of commerce and community, but a civic forum where truth, history, and identity are made visible through form. In these figures, history is not only remembered—it is made sensuously present, aesthetically dignified, and publicly shared.

The women of Kurdistan, cast in bronze and stone, are thus not only honored but rendered eternal in the civic imagination. They are not commemorated as anomalies, but honored as architects of Kurdish endurance and imagination.

In an age when monuments across the globe are contested sites of memory—frequently defaced, debated, or dismantled—Erbil’s statues of women stand apart as a rare example of collective consensus. These statues do not evoke division or nostalgia for bygone power, but rather project aspirations grounded in courage, intellect, and communal pride. They are not static relics of the past but vital expressions of the present, rooted in a cultural continuum that sees history not as distant memory but as living inheritance.

Each figure carved in stone embodies a legacy of resistance, creativity, and leadership, and serves as a beacon for future generations navigating their own paths of agency and identity. In this open-air pantheon—this living museum of stone and soul—Kurdistan does more than commemorate. It speaks with clarity and conviction: here, history has not forgotten its daughters; it walks with them, learns from them, and continues to be shaped by their enduring presence.

Reference:

- Hegel, G. W. F. & Knox, T. M., 1988. Lectures on Aesthetics: Vol. 1. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schäfers, M., 2018. "It Used to Be Forbidden": Kurdish Women and the Limits of Gaining Voice. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, Volume 14(Number 1), pp. 3-24.