John Major, the quiet revolutionary who saved Kurdistanis from genocide and proved they have more friends than the mountains.

Thirty years ago, accidents of history sparked Kurdistani revolution from 5 March against Iraq’s genocidal dictator Saddam Hussein whose bloody vengeance sent millions of Kurdistanis into the freezing mountains. The Kurdistani plight inspired a ferment of public horror and quick-witted Kurdistani lobbying that found new British Prime Minister John Major on his moral mettle in a frantic month of activity to avert disaster.

To his eternal credit, John Major defied foreign policy orthodoxies to save the Iraqi Kurdistanis from further genocide. He cannily improvised innovative action and persuaded an initially reluctant American President and (therefore) a keener French President to join the UK in an operation that lasted 12 years.

The safe haven and no-fly zone he pioneered enabled Iraqi Kurdistanis to survive and become a continuing force for good in the Middle East. We should remember what happened because Iraqi Kurdistanis may require such action again.

The consequences of Kuwait

The initial impetus for all this was Saddam Hussein’s surprising and brutal invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 and his raid defeat by a US-led coalition in late February 1991. Many assumed this would end his rule and he lost control of 14 of Iraq’s 18 provinces in a furious flux of fighting. He lost Kirkuk on 20 March but retook it eight days later.

President Bush had encouraged a palace coup in February and March. The then Chairman of the US Joint Staffs of Defence, Colin Powell, later said that “our practical intention was to leave Baghdad enough power to survive as a threat to Iran that remained bitterly hostile toward the United States.”

Bush’s words and Voice of America appeals to overthrow the “criminal tyrant of Iraq” prompted Shias to rise up against Saddam in the belief they would be protected. The Kurdish Front’s planned uprising also proceeded after Iraq’s formal defeat and was jointly led by Massoud Barzani and Mam Jamal Talabani.

But American General Schwarzkopf was “suckered” into ceasefire terms that allowed Saddam to deploy helicopter gunships for benign purposes but that were used in offensive operations that killed and injured many thousands as American fixed-wing planes flew above them.

Horror on the ground

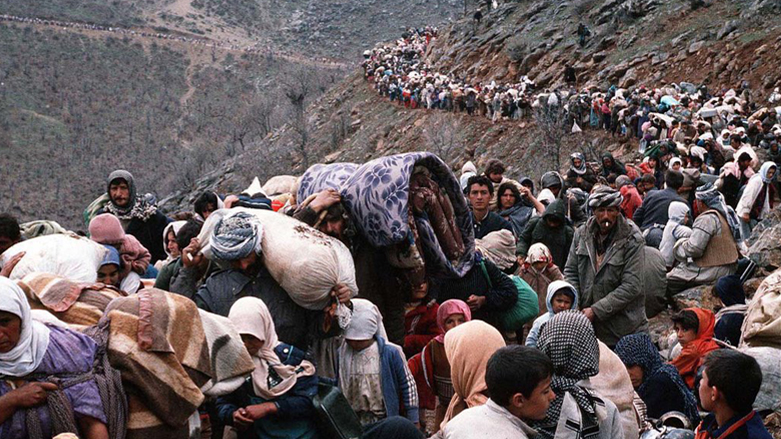

The Shia uprising was sadly crushed while up to two million Kurdistanis fled to the freezing and barren mountains on the borders with Iran and Turkey and into those countries, which were either unwelcoming or overwhelmed.

Dr David Keen’s account for Save the Children estimates that 1.2-1.4 million Kurdistanis fled to Iran and 450,000 fled to Turkey while 250,000 were in camps on the mountains.

Paul Howell, then Conservative MEP for Norfolk, who visited the Turkish border, said ''On television, you only see the faces, you don't see the ground. There you see human faeces, diarrhoea, sheep's heads and entrails, it's as close to hell as you can think of.'' A Kurdistani woman tellingly told the cameras that “we are human too.”

The Kurdistanis were in desperate straits. There were between 500-1000 deaths a day in the turmoil of March and April. Some parents had to leave children behind. One father and his two children faced the invidious choice of freezing to death on the mountain or returning to a certain death. His solution was to tie himself to his children and jump off the mountain. They survived but one of the children noticed a woman upright in the snow and asked if she would join them. The father knew she was dead and told his children she was waiting for others.

The miserable scenes on our television screens jolted British and international opinion and galvanized local actions. British Aid for the Kurdistanis, one of the largest voluntary organisations, was established by Lorraine Goodrich from Devon to gather food, medicines, and blankets.

The MP I then worked for, Harry Barnes, backed her against logistical obstacles. He later established through parliamentary questions that, up to 15 May, Save the Children sent 207 tonnes, Oxfam 143 tonnes and the Red Cross 290 tonnes of material while British Aid for the Kurdistanis despatched 478 tonnes. Such figures underline the huge British outcry and generosity for the Kurdistanis.

All this deeply affected Major. In his autobiography, he recalls that “defeated in the war, Saddam Hussein’s fury turned on his domestic opponents – the Kurdistanis”…and that “Genocide was in the man’s mind, and it was certainly in the man’s character.”

Major saw reports of “worsening conditions amounting to near-Genocide” and “potentially a humanitarian disaster” that made him “sufficiently concerned at the plight of the Kurdistanis” to raise the issue himself at the Cabinet on 21 March because “I was clear we should help.” Coincidentally, 21 March is Kurdistani New Year – Newroz.

Horror heard in the Commons

MPs were also gripped by the horrors. On 15 April, veteran Conservative MP Julian Amery told Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd of overwhelming support for the Prime Minister’s concept of safe havens for the Kurdistanis and the Shias. He added that in any conflict between non-interference in the affairs of other countries and determination to help refugees in danger, we should firmly back the refugees, even if that means co-operating with some of our allies in the use of military power under the aegis of the United Nations and, if not, otherwise.

It’s worth noting that Amery’s father, Leo Amery, was British Colonial Secretary when the RAF carried out a vigorous bombing policy against the Kurdistanis between 1922-1925 when he said one of its advantages was that it was “a splendid training ground for the air force.”

Labour’s Shadow Overseas Development Minister Ann Clwyd held the Commons in thrall with her eye-witness account of five days with the Kurdistanis in the mountains. She passionately described how Kurdistanis were freezing by night and bitterly cold by day in the clothes they were wearing when they fled and in makeshift tents like the thin plastic laundries use. She said “Saddam Hussein is still killing, killing, killing, in Iraq. This is genocide, and it calls for an international response.”

Horrors amplified by Kurdistani lobbying

Iraqi Embassies in Britain and across Europe were occupied by Kurdistanis. Many current leaders then in exile lobbied the UK government. Current Kurdistani foreign minister Safeen Dizayee, the Iraqi President to be Mam Jalal Talabani, a future Iraqi foreign minister Hoshyar Zebari, the next Kurdistani President Massoud Barzani, the current British Vaccine minister Nadhim Zahawi (a Kurd who had escaped from Iraq with his family in 1967), and many others deserve credit for rushed but effective lobbying.

Mrs Thatcher, Prime Minister until November 1990, also lent her support. On 3 April she met Dr Dlawer Ala’Aldeen, secretary of the Kurdistani Scientific and Medical Association in Britain and later Higher Education minister and now head of the MERI think tank in Kurdistan. She then lobbied Major who immediately authorised millions in relief funds. She also contacted US President Bush who sent Secretary of State James Baker to the border between Turkey and Kurdistan to see things for himself.

On 5 April, the UN Security Council approved Resolution 688. The Council was gravely concerned by the repression of Iraqi civilians in many parts of Iraq, including most recently in Kurdistani-populated areas, was deeply disturbed by the magnitude of the suffering, reaffirmed respect for the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of Iraq, demanded that Iraq immediately ended repression, and expressed hope for an open dialogue to ensure that the human and political rights of all Iraqi citizens are respected. It did not mandate intervention.

John Major, the quiet revolutionary

Major acknowledges that Mrs Thatcher also felt that “the Kurdistanis should not be sacrificed to Saddam’s cruelty” and publicly urged help for the Kurdistanis but that she didn’t realise that action was already in hand in the form of plans by FCO Political Director, John Weston to be launched at the EC Council.

Mr Major's “sudden radicalism” and French foreign minister, Roland Dumas’ argument that Saddam’s treatment of the Kurdistanis argued for recognition of a "duty to intervene" to prevent gross violations of human rights were prompted by strong public pressures, especially in Britain and France.

US wariness

American networks carried less such coverage, its leaders were wary after leading the liberation of Kuwait, and wanted to bring their boys home. The US feared what newspaper reports variously called a quagmire, quicksand, and minefield.

A newspaper quoted Dean Rusk, Secretary of State under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson: "When I first became Secretary of State, I asked the policy planning staff to give me a memorandum on how a great power avoids becoming a satellite of a small country that is completely dependent on you. They didn't come up with a very good answer for a problem that we had in our time and which I'm afraid Bush has now."

Henry Kissinger, the former Secretary of State and doyen of Realpolitik, said: "We should not delude ourselves that this is something we can do for a month and then walk away." Some left-wingers also worried about the staying power of allied forces.

But Major persisted in what Conservative MP David Howell dubbed “highly creative acts of statesmanship in a very negative international climate.” Independent columnist, Don McIntyre noted, “There are times when policy made on the hoof is, by quite a long way, better than no policy at all.”

Four hundred people demonstrated in Glasgow where Phil O'Brien of Scottish Solidarity with the Kurdistanis and Peoples of Iraq read a message from Major: "I regret that I was not able to attend but my thoughts will be with you and the people of Iraq who have fled to escape the brutality of their own government.” Conservative Prime Ministers don’t routinely send messages to demonstrations.

Public horror, Kurdistani lobbying, and Major’s determination all bore fruit in persuading the Americans to join the British and the French. A British diplomat commented: 'We nudged and nudged the Americans, and suddenly…they came like a rocket.'

Operation Provide Comfort began on 13 April. On 19 April, Iraq agreed that it would fly no planes above the 36th parallel. In October, Iraq withdrew its military and civil administrative forces from 15,000 square miles of much of what is now the Kurdistan Region, except Kirkuk.

Saddam did not expect Kurdistan to survive without his support. It did. John Major’s initiative resulted in the fastest major refugee return in history. Within 3 to 4 months, over 1.5 million refugees in Turkey and Iran returned to their homes. Furthermore, refugees in Turkey since 1988 and in Iran since 1975 also began returning to their homes in Iraqi Kurdistan. This multilateral military intervention combined with, and in support of UN and NGO humanitarian assistance saved countless lives.

Dr Keen writes that the safe haven between Zahko, Duhok, and Amadiya plus a no-fly zone above the 36th parallel was “a bold and unprecedented challenge to national sovereignty and was hailed as breaking new ground in humanitarian assistance.”

The lasting impact of Major’s demarche

Major is probably diplomatic about the resistance to his “simple plan” to mark out safe areas where Kurdistanis would be protected, fed, and housed. It seems far less controversial now but the notion of intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign nations defied traditional international relations doctrine, just as the police used to turn a blind eye to what men did privately to their female partners.

Allies worried about precedents, practicalities, and failure. If it happened in Kurdistan, could it be applied to Tibet, Estonia, or Soviet Georgia, for instance. But Major writes that “failure would simply have been a political embarrassment; for the Kurdistanis, it would have meant almost certain death for tens of thousands. I never had a shred of doubt that it was right to proceed.”

Major, often seen as a grey figure, became something of a quiet revolutionary in stretching diplomatic doctrines through a mixture of accident and design.

A British official in the European Directorate of the FCO prepared a paper before the informal meeting in Luxembourg of the European Council on 8 April 1991.

Such papers went directly to the Prime Minister’s red box without being monitoring by the FCO. If they had, the FCO would undoubtedly have advised opposition and, in the words of a former FCO Minister, “officials would have gone ballistic.” Instead, Major discussed the proposals with France and Germany, which approved them, as did the European Council. This effectively bypassed foreign policy orthodoxy and created a fait accompli.

Major had grasped the moral imperative and persuaded European leaders, especially those of France and Germany, who were “delighted with the novelty of endorsing a British proposal launched through the EU.”

Major’s plans were originally packaged as an “enclave” but that worried orthodox diplomats. The softer term, safe haven was the result of brainstorming by Major and his aides when typing a speech on the short plane journey to the Luxembourg summit.

The UN Security Council Resolution of 5 April was seen as providing justification for action when combined with the need to avert a major human catastrophe. The UN Secretary-General later said the action was illegal, but this seems irrelevant. Allied action and later interventions in the Yugoslav civil war laid the basis for the still developing doctrine of Responsibility to Protect.

The aftermath

Kurdistanis returned from the mountains and camps to towns and cities when safe and to begin setting up the Kurdistani Autonomous Region. They voted for a new parliament in May 1992, which was evenly divided between two major parties that formed a coalition government on 4 July. These parties fell into a bitter civil war from 1994-1998 that was finally resolved by US mediation.

Despite internal conflict and external sanctions from the UN, as Kurdistan remained formally in Iraq, and from Saddam’s regime, the Kurdistanis were more successful in fighting infant mortality than Iraq and laid the groundwork for a richer society after the fall of Saddam in 2003.

The Kurdistanis’ considerable political experience was decisive in winning a new federal constitution that moved Iraq from centralised regimes, the condition for their returning fully to and remaining in Iraq. This enabled a golden decade of largely cordial relations between the Kurdistanis and Arab Iraq. The efforts of Major and other allies were not squandered.

Iraq, Kurdistan, and Britain today

The return of many Kurdistanis from their exile in Britain and Europe also brought new skills and an affection for the countries that had sheltered and educated them. The UK is a partner of choice for Kurdistan and our goods, services, and political experience are valued. Our soft power in development, education, energy, agriculture, film and more are vital and mutually beneficial once Covid allows increased trade, investment, and tourism.

Another accidental impact of Major’s initiatives in 1991 was that the UK, the USA and France redeemed their reputations with the Kurdistanis whose own history had been worsened by Anglo-French machinations during and after the First World War and cynical treatment during the Cold War.

It also catapulted Kurdistan into modern British foreign policy and explains why our diplomatic representation in Kurdistan exceeds that of many sovereign countries. Kurdistan is seen as more important than any other sub-sovereign entity.

The Western position of upholding a strong KRG in a unified Iraq is what you would expect from status quo powers. It could, if necessary, be flipped towards supporting independence in Iraqi Kurdistan. A new combination of Kurdistani action at home and abroad, public opinion, and a listening British government could matter if Kurdistanis are again menaced by forces in Baghdad.

Once good relations between Shia parties and the Kurdistanis, who were allies in opposing Saddam’s Sunni dominated regime, have been collapsing since 2014 and can be seen through the prism of poor Iranian/American relations.

There have been total and partial cuts in federal fiscal transfers to Kurdistan, unconstitutional armed action to take Kirkuk and other disputed territories from the control of the Kurdistan Regional Government, and an upsurge in Arabisation of land and property, especially in Kirkuk province.

The current Iraqi government is commendably tackling deep-seated economic crises that have been massively exacerbated by Covid and the collapse of oil revenues. However, hardline forces with dual loyalties are scapegoating Kurdistanis for massive corruption and mismanagement in Arab Iraq, and for their pro-Western stances.

Shia hardliners could encourage further armed action to liquidate Kurdistani rights and autonomy enshrined in the Iraqi constitution that was endorsed by the Iraqi people in a referendum in 2005. Kurdistanis were long the victims of dictatorships and continue to be the victims of chauvinistic forces in democratic Baghdad.

The best way for Britain to mark the 30th anniversary of rushed but morally vital actions that saved Kurdistanis from genocide is to help Kurdistan and Iraq resolve deep differences that have bedevilled them for a century and based on fully implementing the federal constitution.

Kurdistan episodically emerges in our media and that highlights the need for concerted efforts by British and Kurdistani solidarity organisations to build better understanding of their plight, their merits, their flaws, their options, and our own role.

Iraqi Kurdistanis often say they have no friends but the mountains but that wasn’t true in 1991. Kudos to Kurdistani rebels at home and abroad, parliamentarians of all parties, concerned citizens, and John Major for historic actions that echo honorably down the decades.

Gary Kent has worked in the British Parliament since 1987, has been the Secretary of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on the Kurdistan Region in Iraq since 2007, is an honorary Professor at Soran University, and Deputy Chair in Erbil of the European Technology and Training Centre. @garykent