Iraqis in US, German courtrooms held for extremist crimes

WASHINGTON DC (Kurdistan 24) – Two men from Iraq faced cases in two courts this month: in two different countries, six thousand miles apart, and thousands of miles from their homes in Fallujah.

Both were involved in violence in Iraq carried out in the name of Islam, although it is questionable whether they were motivated to kill because of their religious beliefs or whether that was a convenient cover for other motives—like a struggle for power and economic resources in post-2003 Iraq or a drive to exercise vicious domination over others.

United States

A detention hearing for one Iraqi – Ali Yousef Ahmed al-Nouri – was scheduled for April 7 in Phoenix, Arizona. The Iraqi government charged that he headed an Al Qaida in Iraq (AQI) cell and was involved in the murder of two Iraqi policemen. Following a 2019 extradition request from Baghdad, US authorities arrested Nouri earlier this year.

Read More: US arrests Iraqi terrorist leader

Although Nouri’s hearing was postponed, more information about him has emerged since his arrest in court papers and press reports.

Nouri is accused of involvement in the murders of two Iraqi policemen in Fallujah. The first murder was in June 2006 and the second in October 2006.

Nouri left for Syria soon thereafter. In 2008, he entered the US as a refugee, and seven years later, he became a US citizen. In 2016, he opened a driving school in Phoenix. According to his lawyer, at some point, he also worked as a cultural advisor to the US military, presumably in Iraq.

People who knew Nouri in Phoenix were surprised at the charges against him. “He’s not religious,” an Iraqi-American, originally from southern Iraq, said. “He was always out partying, drinking. He does not seem to me a person with an extremist background.”

Another Iraqi-American, who owned a Middle Eastern restaurant that Nouri regularly visited, described him in similar terms: “Ali drinks a lot. Ali likes to dance. He’s not religious.”

Fallujah

Bing West, a Marine Corps veteran and Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs in the early 1980s, published a book in 2005 on the fighting in Fallujah the year before: No True Glory: A Frontline Account of the Battle for Fallujah.

“Throughout most of Iraq, the latter days of April 2003 was a time of great joy,” West wrote. “Saddam Hussein’s murderous regime had collapsed.”

“In Fallujah, though, the residents did not cheer when paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division drove into the city in late April,” he continued. “Across the Euphrates south of the city, the large estates of prominent Ba’athists and army officers stood empty but untouched, securely guarded by the curlicue Ba’athist symbol on the courtyard gates.”

“Saddam’s apparatchiks did not consider themselves defeated. They were in temporary hiding,” West stated—contravening the view of the Bush administration that already in May 2003, it had won in Iraq.

In March 2004, a convoy that included four US contractors was ambushed in Fallujah. They were killed, their bodies burned, and their corpses hung from a bridge, precipitating the first battle of Fallujah.

As Brig. Gen. Mark Kimmit (US Army), Deputy Director of Military Operations in Iraq, said then, “Fallujah is a former Ba’athist stronghold which profited immensely under Saddam’s regime, and a small minority of the people there just don’t want it to become part of the new Iraq.”

As US troops moved against the insurgents in Fallujah, Iraq’s interim government, which the US had installed the year before, complained that US airstrikes were killing civilians and doing too much damage to the city.

So the US handed operations over to a “Fallujah Brigade,” led by a Saddam-era general. Within a few months, however, the brigade fell apart, turning over its US arms to the insurgents, and the Marines were obliged to fight a second battle of Fallujah to regain control of the city.

Germany

On Friday, a trial began in Frankfurt, Germany, of a 27-year-old Islamic State member. He, too, is from Fallujah—and was just 11 years old when the battles of Fallujah were fought 16 years ago.

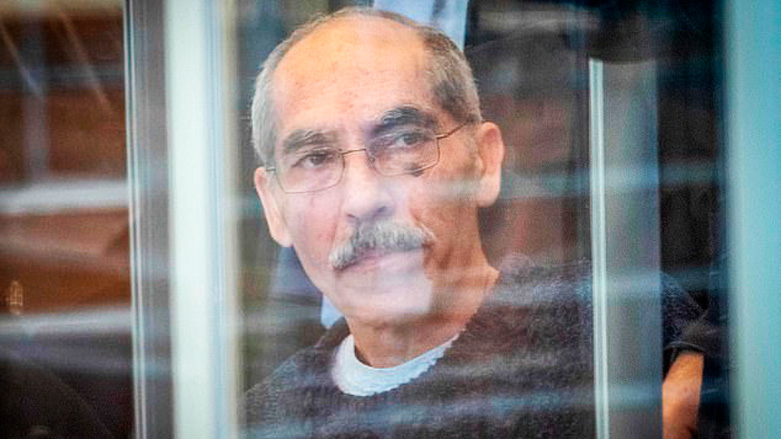

The defendant was identified only as “Taha al-J,” in line with German privacy laws.

The start of this trial marked the start of Germany’s second trial in as many days of individuals charged under the principle of “universal jurisdiction”—which the country adopted in 2002 to help provide for justice in especially horrendous cases, like genocide and war crimes.

Read More: German trial of ex-officials of Syrian regime begins

Taha’s victims were Yezidis – a mother and young daughter – who were seized by the Islamic State in August 2014, when the terrorist group assaulted the Yezidis’ ancestral land in northwestern Iraq, Mount Sinjar.

German prosecutors charged Taha with crimes against humanity, war crimes, murder, human trafficking, and genocide. His trial marks the first time the charge of genocide against the Yezidis has been levied formally against a defendant in a courtroom.

Taha joined the Islamic State before March 2013, the German indictment states (the terrorist group was founded in Syria in 2012, as the civil war there began, by an Iraqi, a former colonel in Saddam Hussein’s military intelligence, as a detailed article, a leak from German intelligence, explains in the highly-regarded news magazine, Der Spiegel).

Taha held various posts in the Islamic State, including in Raqqa, Syria, where he headed something called the bureau of “Shariah exorcism,” the prosecution said, as well as other positions in Turkey, and Iraq.

In 2015, Taha, along with a young German woman, Jennifer W., a convert to Islam, who joined the Islamic State and became his wife, lived in Fallujah.

The terror group instituted the practice of treating Yezidi women as slaves, and in the late spring, Taha bought a Yezidi woman, Nora, and her daughter, Rania, subjecting them to what was essentially torture.

Taha and Jennifer “provided them with insufficient food and water,” the indictment states. They forced them to convert to Islam and “repeatedly beat” them “violently” to “punish and humiliate” them.

At one point, Taha made Nora walk barefoot in the courtyard “in scorching heat,” only allowing her to re-enter the house after half an hour when her feet were painfully burned.

After Rania wet her bed, Taha had her chained outside in the summer heat, without water. The child died.

Col. Norvell DeAtkine (US Army, Retired), former director of Middle East Studies at the US Army’s John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg, advised that Taha’s actions had nothing to do with Islam.

It was “pure savagery,” DeAtkine told Kurdistan 24. His extremism served “to satisfy sadistic impulses,” and “any reasonable and knowledgeable person would recognize that.”

German authorities learned of what had happened to Nora and Rania from Jennifer herself. After Rania’s death, she returned to Germany. But then, she decided to go back to Iraq.

She explained those events to a man whom she believed was going to help her get back there. However, he was really a police informant.

In May 2019, Taha was arrested in Greece, perhaps trying to slip into Europe as a refugee. In October, Greece extradited him to Germany, where Jennifer was already detained and, in fact, on trial for her role in the crimes.

Nora has been a witness in Jennifer’s trial, which is being held separately in Munich. The US-based Yezidi organization, Yazda, helped German authorities find Nora, who is also being assisted by the British-Lebanese lawyer, Amal Clooney, and the Nobel peace-prize winning Yezidi activist, Nadia Murad.

Taha’s trial continues on Monday.

Editing by Karzan Sulaivany