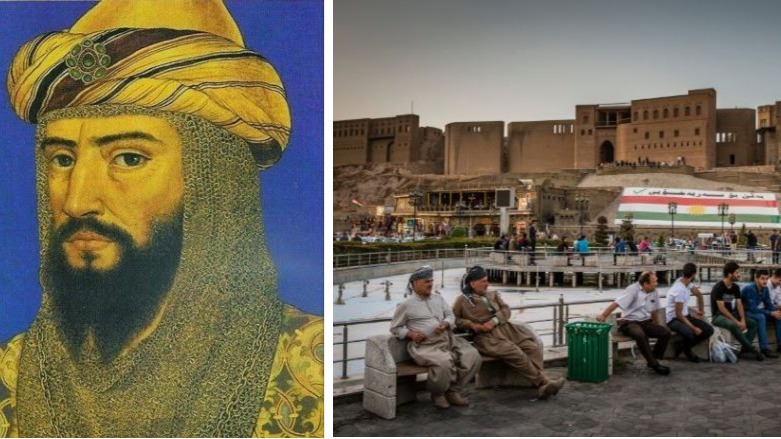

Kurdish inspiration of Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers in tolerance and coexistence: The Sultan Saladin

Saladin, a Kurd originally from the northeast of Kurdistan, established an empire extending from Egypt to the northwest of the Kurdistan Diyarbech/Dirabekir region, to North Africa and Yemen. Thomas Asbridge writes: “Saladin came to this volatile, lethal environment as an isolated outsider – a Sunni Kurd in a Shia world – backed by limited military and financial resources. Few can have expected him to prevail.”[i]

A Jewish intellectual and philosopher, contemporary to Saladin, Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon or Rabbi Moses ben Maimon) was the Saladin court physician. Also, the archbishop of Tyre, known as the historian William of Tyr, knew Saladin as an adversary from the theater of war. Both men admired Saladin for his intellect, leadership, generosity, and tolerance. Saladin’s own court historian, Baha’ al-Din Ibn Shaddad, after Saladin’s death, said: “Never since the time of first khalifs had Islam suffered such a blow.”[ii] Later generations of admiring philosophers, literary artists and historians, just to name a few, included: 13th century (1200 +) Viennese chronicler and poet, Jans der Enikel, author of world history; Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321); Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375); the leading French Enlightenment writer and philosopher Voltaire (1694 –1778); German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781); the English romantic era writer, Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832); Charles J. Rosebault, whose 1930 book, entitled “Saladin, prince of chivalry,” perfectly summarized the qualities of character distinguishing Saladin. The English historian, essayist Alfred Duggan, brought another perspective to the understanding of Saladin in his explorations of his relation and confrontations with legendary English King, Richard Lionheart (2016). Karen Armstrong, a former Catholic nun and Professor of religion, brings a very sober interpretation of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim relations during Saladin’s reign in her book “Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths” (2011). The author of a 2015 biography of Saladin, John Man, described him thus: “It was Saladin’s virtues – his generosity, his magnanimity – that captured the European imagination more than his fighting skills.”[iii]

However, in the Middle East, those values of Saladin are almost totally ignored. Pan-Arabists like Bashar Essad and Saddam Hussein, along with other nationalist leaders and Islamic fundamentalists across the greater Middle East, have been rather abusive of Saladin’s name by representing him as an Anti-Christian, anti-West and anti-Semitic. Many Kurds who are mostly dependent on the Persian, Arabic, and Turkish languages for their knowledge feel strongly to dissociate themselves from Saladin because of that misrepresentation. Therefore, it is important to know who Saladin was, what he represented, and what we can learn from his accomplishments, leadership, exemplary policies of co-existence, and tolerance for diversity, also which represent true Kurdish culture and tradition.

Crusaders of the Saladin era represented almost all of the European military powers from England, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, and most others. Yes, Saladin defeated their combined forces, but this wasn’t his most important accomplishment, as we will see. When Europeans encountered Saladin, they were astonished by his quality, magnanimity, hospitality, generosity, and intellect. They hadn’t previously encountered any such Muslim rulers. The Muslim Sultans before him were mostly Arab or Turk, but Saladin was a Kurd from the heart of Kurdistan. Neither had the Europeans met any Christian Crusader king like him before. At the time, the critical focus was on religious identity and knowledge about different ethnic groups was limited or considered irrelevant. For example, Muslims called all Europeans “Franks” and Europeans called all Muslims “Saracens.” Saladin’s Kurdish background did not become part of his story until around 1700. For example, for Voltaire, Saladin was “from the little province of the Curdes, who have been always a warlike and independent nation.”[iv] Until 1800 some Europeans spelled “Kurds” with “C.” Yes, Kurds were warriors but not warlike because they always had to defend their country and their independence strongly against foreign invaders. Throughout history, Kurdistan has been subject to major power aggression, and Kurds had to defend themselves. Therefore, many historians, from Xenophon (circa 370 B.C.) onward have mostly encountered the Kurds during wars, accounting for why Kurds have been portrayed as warlike people. For example, throughout the 20th century until today, Kurds have been at war with regional countries, and by extension with big powers, simply because they cannot accept foreign occupation of their country and denial of their very existential rights. As Voltaire stated, throughout history, Kurds were always an “independent nation,” and this remained true even until almost a century after Voltaire.

Saladin and Jews

When it comes to Jews, Saladin had a very special place for them. First, he provided refuge to that famous Jewish scholar, Maimonides, from notorious discrimination and persecution in Muslim Spain, and who escaped to North Africa to become a distinguished leader of the Jewish community in Egypt, as appointed by the Sultan Saladin. According to Maimonides’ biographer, Abraham Joshua Heschel, “Maimonides’s position at court was of utmost importance for the Jews of Egypt.”[v] Jews gained prestige and respect. Their Jewish culture flourished. Maimonides and other Jewish intellectuals produced some of their greatest work in Egypt and Israel during the Ayyubid period.

Joseph ibn Aknin, a Jewish physician and teacher from Aleppo, wrote to Maimonides to express his appreciation regarding this new political position:

“When I heard that God, the Almighty, had granted to the Jewish nation the bliss and dignity of this supreme distinction by the appointment of your high person, our master, the great teacher – may his fame be grand and his honor sublime – my joy and jubilation were very great, and I said: For the Lord will not turn away His people or abandon His property.”[vi]

Upon this appointment, the Sultan officially recognized Jewish political rights and leadership, the most important event after Saladin conquered Jerusalem in October 1187. The victor now had to show his greatness, generosity, and tolerance of diversity. Now, action would speak louder than words. Armstrong remarks: “Christians. After the Third Crusade, even Latin pilgrims from Europe would be permitted to come on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Saladin also invited the Jews to come back to Jerusalem, from which the Crusaders had almost entirely excluded them. He was hailed throughout the Jewish world as a new Cyrus.”[vii] The comparison of Saladin to Cyrus shows the level of Jewish appreciation for Saladin. Along with the Prophet Noah, Cyrus is the only other non-Jewish person admired and revered in the Old Testament. “The Prophet Isaiah, in an unparalleled burst of admiration for a non-Jewish monarch, calls Cyrus both the ‘anointed’ and the ‘shepherd’ of God (Isaiah 45:1; 44:28).”[viii] Nothing could be a better representative than this of Saladin’s thinking or attitude about Jews and Jerusalem and the Jewish appreciation of him. Furthermore, his understanding of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam’s relation to the holy city was shown when he allowed Christian Pilgrims, too, to perform their religious duty of pilgrimage after defeating the Christian European forces. This approach of Saladin radically differentiated him from his predecessors in the east and west, among earlier Muslim and Christian victors, and from his Memluk and Ottoman Sultan successors. Before Saladin, the victors took all and punished the losing side severely.

Saladin and Christianity and the West

In western and Christian literature, Saladin is consistently portrayed as just, intelligent, generous to an extreme, and merciful to enemies even in the battlefield and to prisoners of war. His equal treatment of Christians, Jews, and Muslims and his tolerance are common themes from the Saladin era until today.

One of the most discussed subjects is Saladin and Richard Lionheart, King of England and the leader of Crusaders. It is clear that Saladin didn’t see the King of England as his equal; therefore, when Richard wanted to meet with the Kurdish Sultan, Saladin referred Richard to his brother Saphadin, who was the second in command of Saladin forces.[ix] There is no record or data that the Sultan ever killed any prisoner of war or unarmed men after conquering his enemies.[x] In the battlefield, Sultan Saladin’s noble acts were exceptional. When his enemy Richard’s horse was killed in the battlefield, and he fell with his horse, Saladin sent him two horses as a gift.[xi] One of the battlefield witnesses, the historian Archbishop William of Tyre, “believed that the Ayyubid ruler posed a grave and immediate threat to the continued survival of Outremer, but nonetheless commended him as ‘a man wise in counsel, valiant in battle and generous beyond measure.’”[xii] Clearly, this is an exceptional remark, perhaps one of the greatest honors to be mentioned by one’s enemy in this way. There are not many kings in world history to be so admired by their adversaries.

Taking Jerusalem and victory against the King of England and Europe

Saladin took Jerusalem, which had been under European rule since 1098, from the Crusaders in 1187. The Kurdish Sultan’s action during and after the liberation of the holy city probably had its biggest impact on the general population of Christians and Europeans because his action had a direct impact on their life and existence.

Voltaire wrote in 1759 about the Kurdish King’s treatment of prisoners of war after his victory: “…when the captive king, who expected nothing but death, was astonished at being treated by Saladin…as prisoners of war are now treated by generals of the greatest humanity…Saladin with his own hand presented Lusignan a cup of liquor cooled with snow.”[xiii] For the general population, the Kurdish King was no less generous and humane. Voltaire continued: “On his making his entry into Jerusalem, many women came and threw themselves at his feet; some begging that he would restore to them their husbands, and others their children or their fathers, who were his prisoners; and he granted their requests with a generosity, of which that part of the world had yet afforded no example.”[xiv]

The above example from one of the greatest thinkers and philosophers of enlightenment gives us enough idea how the great Kurdish King acted during and after a war with prisoners of war and their relatives. But to have a better understanding, one could compare the Crusaders’ action in 1098 when they took the holy city from the Muslims. “The Christian crusaders who took the city in 1098 slaughtered every inhabitant of the city, as opposed to Saladin who spared the inhabitants.”[xv] This generosity of the Kurdish King had a great impact on European public opinion when they returned to their homes across the European continent and the English Islands.

King Saladin’s adherence to treaties and his promises are not less legendary. Karen Armstrong wrote after the victory in Jerusalem and evacuation of Christians from the city:

“When the Muslim historian Imād ad-Dīn saw Patriarch Heraklius leaving the city with his chariots groaning under the weight of his treasure, he begged Saladin to confiscate this wealth to redeem the remaining prisoners. But Saladin refused; oaths and treaties must be kept to the letter. ‘Christians everywhere will remember the kindness we have done them.’ Saladin was right.”[xvi]

Yes, Saladin has become a true legendary hero for Europeans since then. He became the subject of heroic folktales, poems, and stories, from romance to chivalric questing. For religious thinkers, he was a great example of ethical, non-materialistic, exemplary leadership. For renaissance and enlightenment thinkers, Saladin was a source of inspiration for toleration and appreciation of diversity. Sir Walter Scott, in the introduction to his romantic novel “The Talisman,” compares King Richard Lionheart and Kurdish King Saladin: “Christian and English monarch showed all the cruelty and violence of an Eastern sultan, and Saladin, on the other hand, displayed the deep policy and prudence of a European sovereign.”[xvii]

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri, the greatest Christian philosopher of the 14th century, in his famous writing “The Banquet” (1307), equates Saladin with Alexander the Great. He wrote: “Who lives not again in the heart of Alexander because of his royal beneficence? Who lives not again in the good King of Castile, or Saladin, or the good Marquis of Monferrat…when mention is made of their noble acts of courtesy and liberality?”[xviii]

In “Divine Comedy or Inferno” (1320), Dante places the Kurdish King in the same category with Socrates and Plato among other non-Christian virtuous leaders and philosophers.

“And saw alone, apart, the Saladin.

When I had lifted up my brows a little,

The Master I beheld of those who know,

Sit with his philosophic family.

All gaze upon him, and all do him honour.

There I beheld both Socrates and Plato…”[xix]

He saw Saladin alone because there wasn’t any other in his category from the Middle East or the Muslim world. David Van Biema of Time magazine nicely summarized Dante’s’ mention of Saladin; “a man who had made his name successfully battling Christianity would be lionized by the author of perhaps the most Christ-centered verse ever penned.”[xx]

The Kurdish King equal treatment of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

Again, and in contrast to current Islamist and Arab or Turkish nationalist propaganda, Western thinkers believed Saladin treated the three religions equally. Some well-known stories have been written by distinguished thinkers to illustrate this. One was by the 13th-century German Viennese historian and poet Jans der Enikel,[xxi] and another was by 14th century Italian Renaissance humanist writer and poet Giovanni Boccaccio. A third is by Voltaire, writing in 1759, about 500 years afterJans der Enikel.

Boccaccio in “the Decameron”[xxii] tells the story of Melchisedech, a Jewish businessman’s encounter with the Kurdish King who challenges him about which religion is superior to others. The businessman tells the story of “three rings” to the King. The moral of the story was that all three religions are equal and only God could decide which one was better. Melchisedech’s intelligent story received Saladin’s appreciation, and they became very good friends.

Jans der Enikel and Voltaire’s writings focus on a common point. Before Saladin passed away, in his will, he determined that whatever his estate left was to be equally divided among Jews, Christians, and Muslims. By doing this, in the words of Voltaire, he showed “that all men are brethren.”[xxiii]

Saladin’s tolerance and co-existence philosophy in Performing Art theaters

German thinker and writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, in 1779, wrote his famous play on religious tolerance and co-existence “Nathan the Wise.” The play takes place in Jerusalem during the Saladin era. It shows how Christians, Jews, and Muslims, despite their differences and conflicts, came to love each other as one family.

When the play was written in 1779, it was not initially allowed to play or to be published in Germany because of opposition from the Church, but later it became popular. Today, the topic remains very important across the globe; therefore, in the spring of 2016, this play was performed on Broadway, in New York City. In some colleges in the USA, “Nathan the Wise” is taught in performing arts classes, and productions are staged. For example, it has been performed and will be performed again on Nov. 7, 2018, at Montgomery College, in the United States.[xxiv]

In a review of the play when it was performed in Broadway, the New York Times (NYT) writer Charles Isherwood stated: “We cannot fail to note the relative amity with which the characters coexist, despite their stark religious differences and casually proclaimed prejudices, in comparison to the conflict that divides Jerusalem today, and of course the increasingly dangerous problem posed by fanatical Islamists.”[xxv][xxvi] Clearly, one could see in Saladin one of the best antidotes to current trends in Islamic fundamentalism and intolerance in all kinds of religion.

The study guide for the play summarizes very well: “Nathan the Wise demonstrates that unity and harmony are possible even among persons of diverse backgrounds. Consider that Saladin and Sittah are Muslims. The knight is the Christian son of Saladin’s brother, Assad, a Muslim. Recha is the daughter of a Muslim, Assad, but was baptized a Christian and reared by a Jew. As Assad’s brother, Saladin becomes the uncle of the knight and Recha, and Sittah becomes their aunt. Nathan is the adoptive father of Recha and thus a non-blood brother of Saladin and Sittah. They all become one family at the end of the play.”

Saladin was a product of Kurdish tradition and Culture

Just as Europeans were surprised by Saladin’s magnanimity, they were to some degree similarly surprised by the behavior of the Kurdistan Region. When the Islamic State (IS) attacked Iraq and Iraqi armed forces collapsed and withdrew, religious and ethnic minorities rushed to the Kurdistan Region for protection. On June 26, 2014, Al Jazeera TV’s web page headline was “Iraq’s Christians seek refuge with Kurds.”[xxvii] Sometimes one could see headlines like this in the international media, “Iraq’s Kurds urge Jews, other religious minorities to come, practice faith.”[xxviii] According to US House Representative GusBilirakis, “The Kurds now formally recognize eight religious minorities, giving them a voice and an avenue for official cooperation within government.”[xxix] Kurdish traditions, despite everything, still survive in these matters. When one browses through international media, one can find hundreds of similar examples since the IS war started.

Finally, when IS was defeated, many Sunni Arabs including some IS militants themselves, sought refuge and asked for “mercy” from Kurdistan’s armed forces, the Peshmerga, because they didn’t trust the Iraqi Shia Arab-led government would treat them fairly. On Oct. 1, 2016, the NYT reported, condition of people fleeing the IS stronghold Hawija during the Iraqi army and Iranian proxies attack; “While civilians from the stronghold, the city of Hawija, have sought safety in Kirkuk and elsewhere in Iraq’s Kurdish region, this past weekend was the first time they came in large numbers with men of fighting age.”[xxx] They knew they could trust Kurdistan Peshmerga for better treatment as prisoners of war or as refugees or internally displaced people.

In 2014, Time Magazine declared Masoud Barzani, the then-President of the Kurdistan Region, and the Commander of Kurdistan’s armed forces the Peshmerga, “Person of the Year.” The article identifies the father of the President: “Mustafa, the most famous Kurd since the 12th-century general Saladin.”[xxxi] Clearly, Barzanis are not just the most famous Kurds but have demonstrated they preserve the Kurdish, and Saladin’s, tradition of tolerance and peaceful co-existence.

In summary, Saladin had demonstrated the importance of laws, treaties, compassion, merciful treatment of prisoners of war, and hospitality. Those values are greatly needed in international politics and relationships. Every day, we see an erosion of domestic and international laws across the globe. However, in Iraq, Syria, and most of the Middle East, lawlessness and violations of treaties and constitutions are almost sources of pride for some of the rulers. Tragically too, many of these are supported by the international community or silently approved.

Considering the global trends in political and religious intolerance, xenophobia, anti-immigrant and anti-refugee hysteria, and discrimination against displaced people, we need Saladin more than ever. There have been many Kings, Sultans, Emperors, before and since Saladin, but only a few have left such a legacy. Since the 12th century, Saladin’s example continues to impact our thinking, from the Middle Ages, through the Renaissance, and Enlightenment, until today. I wish “Nathan the Wise” could be played in every city in Kurdistan and all other countries.

Amed Demirhan is internationally recognized with multiple awards in librarianship. Multilingual, he holds a Master of Arts degree in Library and Information Science (MLIS) from the University of Southern Mississippi (USM), a Master of Arts in Dispute Resolution from Wayne State University (Detroit, MI), and a BA in International Studies with a minor in Spanish (USM).

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Kurdistan 24.

Editing by Karzan Sulaivany

***

[i] Asbridge, Thomas. The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land (p. 275). Harper Collins e-books. Kindle Edition.

[ii] Quoted by Man, John (2015) Saladin The Legend, The Life, And The Islamic Empire (P. 315)

[iii] Man, John (2015) Saladin The Legend, The Life, And The Islamic Empire (P. 346-7).

[iv] Voltaire,1. (1759). An essay on universal history, the manners, and spirit of nations: from the reign of Charlemaign to the age of Lewis XIV. 2d ed., London: Printed for J. Nourse. (P. 368)

[v] Heschel, Abraham Joshua. (1983) Maimonides: A Biography (p. 220). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition.

[vi] Heschel, Abraham Joshua. Maimonides: A Biography (p. 184). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition.

[vii] Armstrong, Karen. (2011) Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths (Kindle Locations 5812-5815). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[viii] Telushkin, Joseph. (2010). Jewish Literacy Revised Ed: Jewish Literacy Revised Ed: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History (p. 176). Harper Collins e-books. Kindle Edition.

[ix] Duggan, Alfred. Richard and Saladin (2016) (Kindle Locations 91-94). New Word City, Inc.. Kindle Edition

[x] Duggan, Alfred. Richard and Saladin (2016) (Kindle Locations 62-63). New Word City, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

[xi] Duggan, Alfred. Richard and Saladin (2016) (Kindle Locations 173-177). New Word City, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

[xii] Quoted by Asbridge, Thomas. The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land (p. 335). Harper Collins e-books. Kindle Edition.

[xiii] Voltaire,1. (1759). An essay on universal history, the manners, and spirit of nations: from the reign of Charlemaign to the age of Lewis XIV. 2d ed., London: Printed for J. Nourse. (PP. 368-9)

[xiv] i.e. P.369

[xv] David, Brian C., "Inventing Saladin: The role of the Saladin legend in European culture and identity" (2017). Masters Theses. 502. (David 2017 P.30 – foot note)

http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/502

[xvi] Armstrong, Karen. (2011) Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths (Kindle Locations 5749-5751). Random House Publishing Group Kindle Edition.

[xvii] Scott, Sir Walter. (1832) Walter Scott. The Talisman (Kindle Location 119). The Talisman (Kindle Locations 68-69).

[xviii] Dante Alighieri. (1307) The Banquet (Il Convito) (Kindle Locations 2252-2255).

[xix] Dante Alighieri. (1320) DIVINE COMEDY - INFERNODANTE ALIGHIERI (translated by HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES) (PP. 27 – 28)

Retrieved Sept. 12, 2018, from Dante Alighieri - Divine Comedy, Inferno https://www.paskvil.com/file/files-books/dante-01-inferno.pdf

[xx] Biema, David Van (Time. Dec. 26, 1999) Saladin (c. 1138-1193)

Retrieved Sept. 12, 2018, from http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,36516,00.html

[xxi] Man, John (2015) Saladin The Legend, The Life, And The Islamic Empire (PP. 343 -345)

[xxii] Boccacio, Giovanni. The Decameron Novel 3 Coradella Collegiate Bookshelf Edition

Retrieved Sept. 19, 2018, from http://flc.ahnu.edu.cn/uploads/20170316/20170316130900_93144.pdf

[xxiii] Voltaire,1. (1759). An essay on universal history, the manners, and spirit of nations: from the reign of Charlemaign to the age of Lewis XIV. 2d ed., London: Printed for J. Nourse. (P. 374)

[xxiv] Montgomery College: Performing Arts Department / Rockville

Retrieved Sept. 20, 2018, from https://cms.montgomerycollege.edu/EDU/Department2.aspx?id=13060

[xxv] By Isherwood, Charles (2016, April 13). ‘Nathan the Wise’ Brings a Morality Tale to Today” New York Times.

Retrieved Sept. 19, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/14/theater/review-nathan-the-wise-brings-a-morality-tale-to-today.html

[xxvii] Salih, Mohammed A. (2014, June 26.) Iraq's Christians seek refuge with Kurds. Al Jazeera.

Retrieved Sept. 21, 2018, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/06/iraq-christians-seek-refuge-with-kurds-2014624867119947.html

[xxviii] McKay, Hollie (2016, May 09) Iraq's Kurds urge Jews, other religious minorities to come, practice faith. Fox News.

Retrieved Sept. 26, 2018, from http://www.foxnews.com/world/2016/05/09/iraqs-kurds-urge-jews-other-religious-minorities-to-come-practice-faith.html

[xxix] Bilirakis, Gus . (2016. May 4) A call to action for religious freedom Washington Times.

Retrieved Sept. 26, 2018, from https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/may/4/gus-bilirakis-aiding-refugees-from-religious-oppre/

[xxx] Nordland, Rod. (2017, Oct., 1) Captured ISIS Fighters’ Refrain: ‘I Was Only a Cook’. New York Times.

Retrieved Sept. 26, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/01/world/middleeast/iraq-islamic-state-kurdistan.html

[xxxi] Vick, Karl (2014, Dec. 10) Person of the Year Massoud Barzani Time

Retrieved Sept. 26, 2018, from http://time.com/time-person-of-the-year-runner-up-massoud-barzani/