New book highlights life story of Kurdish female fighter from Iran

LONDON (Kurdistan 24) – A new book tells the fascinating personal story of 55-year-old Diana Nammi, one of the first female members of Kurdish opposition forces in Iranian Kurdistan (Rojhilat) that fought against the Iranian regime starting in 1979.

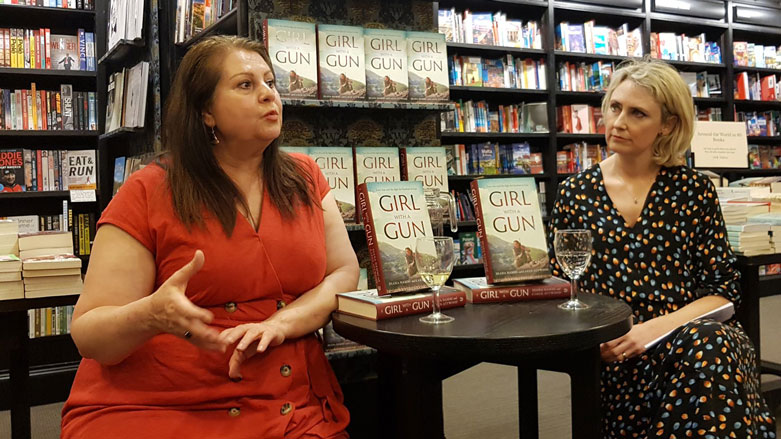

Girl With a Gun, published on March 5, was co-written by British journalist Karen Attwood and covers decades of Nammi’s storied life in her own words.

Nammi was initially inspired by her father to stand up for women's rights at the age of four. She witnessed him stepping forward to save a woman’s life on her wedding day when she was threatened with death because she was allegedly not a virgin. From this day forward, she says, Nammi learned that one person could change the world around them.

After the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the fall of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Nammi decided to join Kurdish Peshmerga forces after the new Islamic regime attacked members of the nation's Kurdish population.

She was part of the Kurdish Komala party, which formed one of the first mixed-gender battalions in the 1980s. For over 12 years, she served in with them before fleeing to the United Kingdom as a political refugee.

There, she founded the Iranian and Kurdish Women’s Rights Organisation (IKWRO) in 2002, an organization that aims to support women from the Middle East and Afghanistan who have faced honor killing or other gender-based violence.

“For 12 years, I was a Peshmerga in Kurdistan and 18 years a Peshmerga in the UK,” she told Kurdistan 24 after a discussion event held at a London bookstore.

After all these years, she said, she decided to write the book because Kurds as a people have “many untold stories.”

“The Kurdish people fought for years or years, but we have very few written stories and very little written history. So, I thought that this is my duty, actually, to write about our history, especially about women and our role in fighting against these brutal regimes in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria.”

“I think it’s a great experience for other women and new generations to learn from that and the things we have done,” she continued.

“I am hoping it will encourage other women and other men and those who really fought for human rights, equality, socialism, and freedom, to bring their experiences together. We need to make sure all the world is hearing about our battle and our fight for equality, for freedom, for people’s rights, for human rights, for Kurdish rights.”

She said her book is still important today since Kurdish women continue to fight as Peshmerga forces. “Still, we’ve got those regimes who are oppressing the Kurdish people. It’s a part of our experience and I am hoping it will be useful for our community, the society, and for the world.”

In Iran, not much has meaningfully changed for Kurdish rights since Nammi first arrived in the UK. According to a UN Human Rights report released in August, the provinces inhabited by an estimated eight to ten million Kurds in Iran are characterized by a lack of economic development and high unemployment rates.

Read More: UN Special Rapporteur says half of Iran’s political prisoners are Kurds

Furthermore, Kurds do not receive education in their mother tongue and a large percentage of political prisoners in Iran are Kurdish. Kurds also constitute a disproportionately high number of those who received the death penalty.

While Kurds in northeast Syria and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq have enjoyed recent increased visibility in international media, largely because of their crucial part in the war against the Islamic State, the Kurdish plight in Iran still gets scant coverage, in large part because there is no press freedom there.

Nammi’s book is her part in ongoing efforts by other displaced members of her community to educate others on Iranian Kurds, or in Kurdish, Rojhilatis.

“I hope things will change in Iran as well as in Rojhelat in the media and they get attention, but the whole political situation is different than in other parts of Kurdistan.”

Editing by John J. Catherine