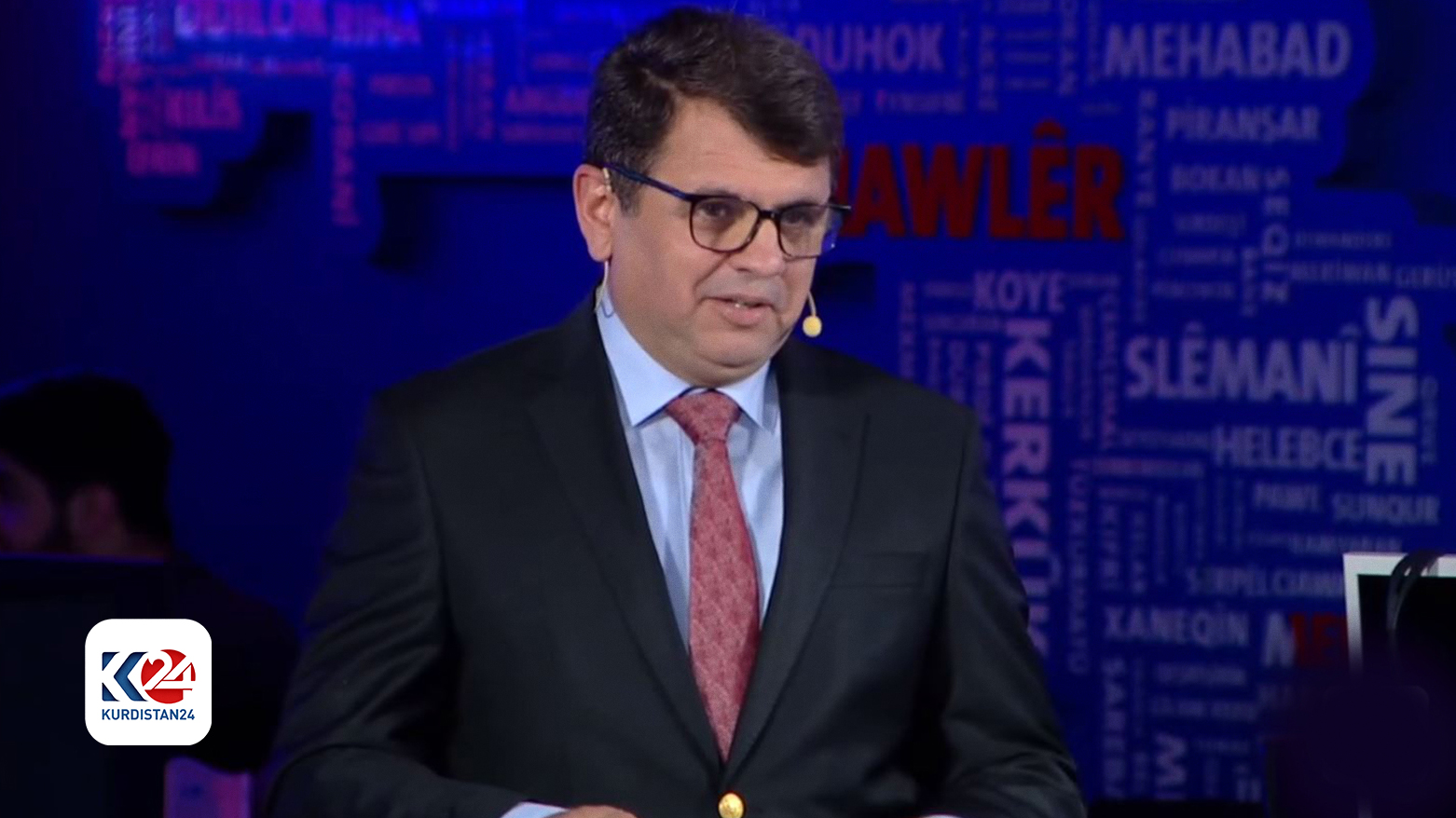

Kurdistan 24 Director General Publishes article in Gold Institute for International Strategy

Erbil (Kurdistan 24) – In an article published in the Gold Institute for International Strategy, a Washington, D.C nonprofit think tank addressing emergent national security issues, Director General of Kurdistan 24 Media corporation Mr. Ahmed Zawitey discusses the status of Kurdistan Region on a global stage.

You could access the article here: Iraqi Kurdistan...The Weakest Link At The Center Of The Struggle Of The Powerful

Mr. Zawitey highlights the fact that throughout the entirety of the twentieth century, Kurdistan Region has been exposed for more than seventy years to wars between the Kurdish nationalistic movement demanding its rights to self-rule in Iraq.

The history of the Kurdistan Region, as Mr. Zawitey pointed out, is the history of continuous struggle to achieve self-rule, from the time of monarchy in the forties and fifties to the Abdul Karim Qassem and Abdul Salam Arif in the Sixties and the dark rein of Saddam Hussein through eighties.

However, Zawitey raised a simple question which is hard to answer; how, amid such turmoil and mayhem, did Kurdistan Region manage to “endure for more than 32 years?”

Kurdistan Region has had to confront plenty of hurdles and impediments in its transformation into the most stable region in Iraq. Mr. Zawitey highlights such stability in Kurdistan Region has helped it to become a stable center “in terms of security and economic development, particularly after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003 by American forces.”

In another part of his article, Mr. Zawitey emphasizes the fact that Kurds do acknowledge their history of struggle; from the brutal and tormenting years of Saddam Hussein regime to the war against ISIS, Kurds pushed through and emerged victorious.

He points out that, whether it was the follow-up to the ISIS defeat or the post-Iraq-Iran war, the euphoric feeling of “victory” instilled a sense of power in the army and armed militias. In both cases, and as result of such enraptured feeling, the Iraqi army targeted Kurdish territory.

However, Zawitey notices that, “When the Kurdish side is not strong in many aspects, it remains strong in terms of its historical memory, which preserves images of tragedies that are replicated from one decade to another, a memory that led him to feel that a threat similar to what happened in 1988 was returning again from the south.”

Having the bitter memory of Saddam Hussein regime in mind, Zawitey says, the Kurds “hastened steps to proceed with a referendum on its independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017”, which was to “eradicate this ever-present threat”.

The lack of international support was “lamentable” and the neighboring countries, threatened by the prospect of a strong Kurdish state, “strangled the region within itself,” he wrote.

Following the suspension of the Referendum results, Kurdistan Region resorted to diplomacy to “preserve what remained of the region and its powers, but hostile steps by Baghdad against the region continued and intensified,” Zawitey added.

He reminds us of those “hostile steps”:

1. Weakening Kurdish presence in Baghdad and strengthening Shiite strength in the government created suitable ground for increasing hostilities toward Kurdistan Region.

2. The repeated bias in Federal Court measures against the region culminated in limiting the KRG powers. Mainly through these two verdicts:

* “Canceling the Kurdistan Parliament’s ability to hold elections, the date of which has not yet been set. Indeed, the court, itself, is postponing the holding of these elections under various pretexts, and thus, the Iraqi Kurdistan region is currently undergoing a period of legal vacuum.”

* “Preventing the Iraqi Kurdistan region from exporting its oil, thus leaving the region without a budget.”

3. The third step was to refuse the disbursing of the Kurdistan region’s share of the Iraqi budget,” including disbursing employee salaries, thus harming the economy in the region, which was in a better condition than the rest of the Iraqi provinces more than a decade ago”.

However, Zawitey argued in the article that the hostility did not just stop there, rather it “reached the most precarious step threatening this region, which is the bombing of it and its civilian facilities by bomb-laden drones via militias affiliated with Iran.”

He argued that Iranian ballistic missile attacks on the regional capital, Erbil, under false pretext of the presence of Israeli Mossad sites, the baselessness of which was also reiterated by multiple committees of investigation to the targeted locations, were a dangerous escalation of matters.

Zawitey stated that “KRG is the only region in Iraq which has not yet submitted to Iranian-directed demands, as opposed to the Shiite and some Sunni groups in Iraq.”

He continued by arguing that despite inter-party disagreements, Kurdistan Region, under wise leadership, has been able to evade and elude Iranian influence.

Iranian propaganda following the ballistic attacks was deceptive. Zawitey argued, “It [Iran] knows before anyone else that they are not Mossad sites. In fact, it could be argued that if such Mossad sites existed, Iran would not have dared bomb them.”

Zawitey supposed that the main reason behind the Iranian attacks was in fact to “forcefully align Erbil, specifically the Kurdistan Democratic Party and its head, Masoud Barzani, to its side, just like other Iraqi Shiite and Sunni leaders.”

This could give Iran the dream corridor and ensure “the formation of the Shiite crescent extending from Qom, through Iraqi Kurdistan, all the way to Qamishli in Syria,” he added.

By bombing Erbil, Iran wanted to, first, remove the impediment to its regional control, namely the Kurdistan Region. Second, “a posturing message to the Americans about the range of distances that Iranian missiles can travel and the accuracy of the target of these missiles” he observed.

Mr. Zawitey mentioned in the article that after the Iranian attack on Erbil, the United States conveyed a diplomatic message to Iraqi Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein.

Although the specific details are undisclosed, leaks suggests that “the message is about the ongoing negotiations between the two sides regarding the steps of the American withdrawal from Iraq, and the threat of the return of ISIS, and the transformation of the relationship from being a relationship of militarily supporting the Iraqi side to a normalized relationship,” he wrote.

He argues that even though Iraq and the US seemed to have positive negotiations, however the Iranian-backed militias in Iraq, responsible for deploying explosive drones on US bases, specifically in the Kurdistan Region rejected the American message. They announced “they will not follow this message and will not give it credence, and shall continue targeting American sites,” he exposed in the article.

Another issue in which Zawitey points out is the possibility of the resurgence of ISIS.

For the United States, he argued, the situation extends beyond mere threats. “When Iran is able to forcefully send direct and indirect threatening messages, the Americans also have their own way of responding,” he wrote.

Zawitey explained that the warning issued to Iraq by the U.S., hinting at the resurgence of ISIS, suggests that American troop withdrawal and the conclusion of their alliance could inadvertently facilitate a comeback of ISIS, marking what might be termed as the second phase of ISIS threat.

He argued that from the American perspective, just as Iran engages in an indirect conflict through proxy groups, the U.S. could take a “similar step, which is to pave the way for the return of ISIS to fight the groups loyal to Iran, and perhaps in the future, an ISIS war inside Iran itself, similar to the last operation that killed more than a hundred people inside Iran.”

So what could be the impact on Iraq and the Kurdistan Region?

As the status quo between the U.S. and Iran persists, Zawitey wrote, its ramifications on Iraq's domestic affairs deepen, exacerbating unresolved issues between Baghdad and Erbil. Consequently, the Kurdistan region of Iraq finds itself particularly vulnerable, experiencing its most challenging period in over a decade.

As faced by threats, challenges and growing pressures from its aggressors, the Kurdistan region perceives itself in a predicament, facing a barrage of economic, moral, military, and political pressures.

Zawitey argued that in response, the region has hinted at leveraging its strategic options, one of which includes reconsidering the suspension of the independence referendum results from seven years ago, a vote that saw over 90% of participants favoring independence.

Zawitey argued that the decision to pursue independence, however, hinges on several critical factors:

1. The Americans support this option, and this is not excluded if the Iraqi government continues to request the Americans to withdraw, and Iran and the Iranian militias continue their policies towards the region and the Americans.

2. Turkey’s support for this option in exchange for signing alliance cooperation between Turkey and the region, so that the region fully joins the Turkish decision to adopt its agendas in the region. There is no choice left for Turkey if Iran continues its hostility to the region, except for the region to withdraw to its side because the region represents an important depth for Turkey.

3. International, American, and perhaps Turkish permission for the region to re-export its oil for Baghdad has continued to prevent the export of this oil and the region has remained without a budget.