Feyzeddin Donmez

Writer

ROJAVA’S PAIN MAY BE THE KURDS’ POLITICAL AWAKENING

Political scientist Feyzeddin Donmez argues that the recent political betrayal of Rojava, while a tactical setback, is forging an unprecedented strategic unity among Kurds, centered on the fundamental vulnerability of statelessness.

The most consequential moments in a people’s political history are not always victories. Often, they are betrayals.

On January 18 , 2026, a proposed agreement circulated by Syria’s new, unelected president Ahmed al-Sharaa, now presented as Syria’s new political authority, was publicly praised by the western allies before Kurdish leaders had even signed it. The agreement was framed as consensual, despite the fact that General Mazloum Abdi, commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), was not present in Damascus and had not agreed to its terms.

This was not diplomacy. It was imposition.

When Mazloum Abdi traveled to Damascus the following day to negotiate directly, the outcome confirmed Kurdish fears. Syria’s new leadership refused to meet even the most basic Kurdish demands: constitutional recognition, decentralized governance, or meaningful guarantees for political and cultural rights. Abdi returned to Rojava with a decision that surprised some observers but resonated deeply among Kurds: resistance was preferable to a one-sided agreement that stripped Rojava of dignity without offering security.

In the short term, this decision carries real risks. Rojava faces military pressure, economic suffocation, and abandonment by Western allies for whom Kurdish forces sacrificed thousands of lives in the fight against ISIS. That the same allies now appear willing to accommodate an emerging, regressive regime in Damascus, rebranded for geopolitical convenience, has left many Kurds disillusioned.

Yet history suggests that political maturity is rarely born of comfort.

Even if Rojava’s resistance is ultimately crushed, or its leaders are forced into a settlement that falls far short of Kurdish aspirations, something irreversible has already occurred. The trauma of abandonment, by allies, by the international system, and by the regional order, has produced a level of Kurdish unity unseen in generations.

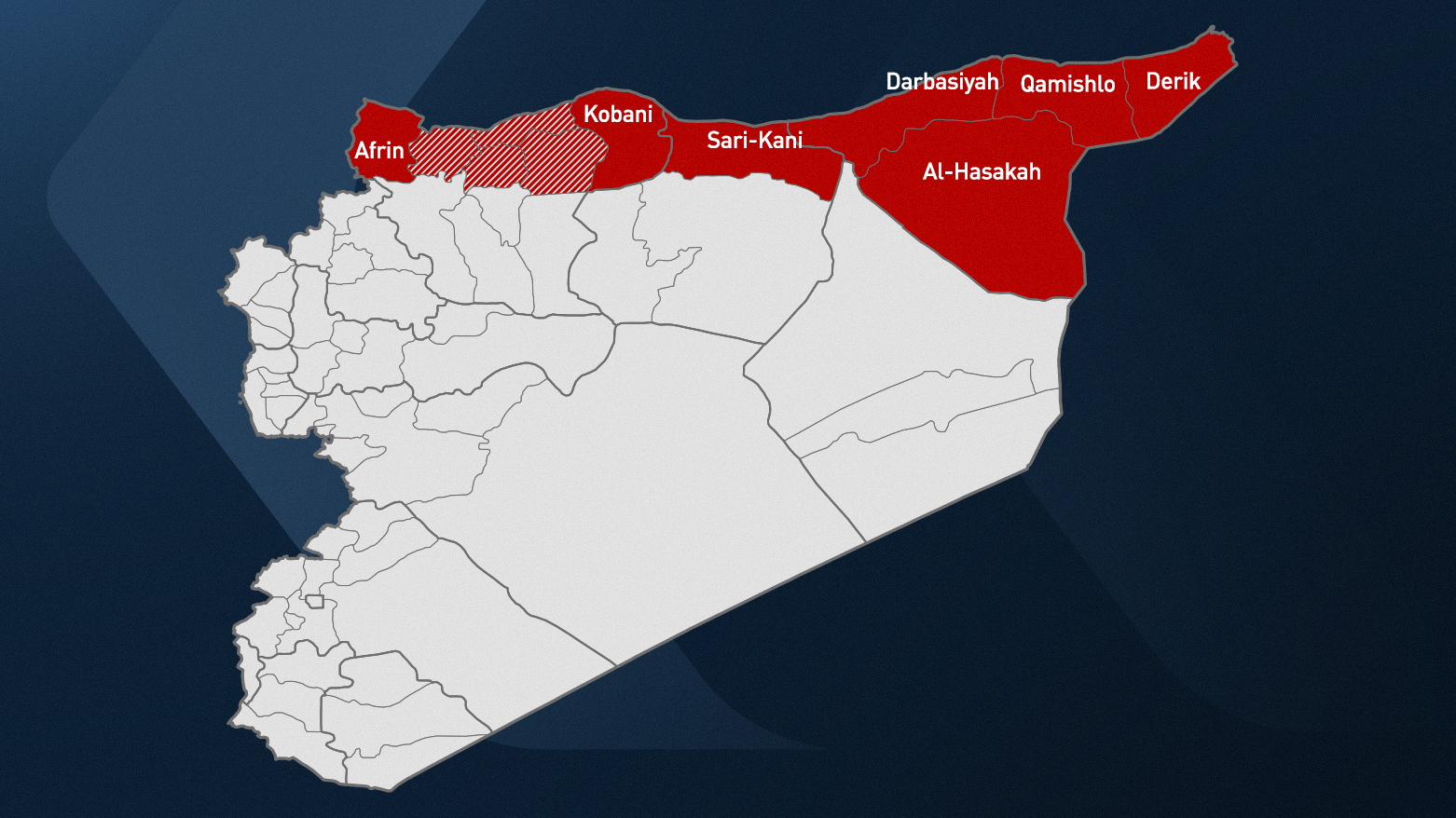

Across ideological, religious, geographic, and political divides, Kurds are reacting not as fragmented communities but as a single people. From Amed to Mahabad, from Erbil to Qamishli, from London to Paris, from Berlin to Vienna, from D.C to Ottawa, and throughout the diaspora, Kurds increasingly recognize a shared truth: their vulnerability is not rooted in ideology or leadership, but in statelessness itself.

Technology and globalization have accelerated this realization. Kurds today are closer to one another than their adversaries, or their so-called allies, understand. Social media, digital organizing, and transnational networks have collapsed the artificial distances imposed by borders. The old divisions, left versus right, secular versus religious, tribal versus urban, are losing their power to obscure the central issue: Kurds remain second-class citizens wherever they live because they lack a state of their own.

This moment, painful as it is, represents a milestone in Kurdish political consciousness. Kurds are learning realpolitik the hard way. They are learning that no external power will safeguard their future, that alliances are transactional, and that they are often valued only as temporary instruments in other people’s wars. Most importantly, they are learning that their greatest source of power, the closest thing they possess to a nuclear deterrent, is unity.

This awakening also signals a shift in Kurdish politics itself. For decades, Kurdish political parties and leaders have shaped the national agenda from the top down, often constrained by regional powers or internal rivalries. Today, the pressure is reversing. Kurdish public opinion, galvanized by Rojava’s ordeal, is beginning to shape leadership rather than defer to it. The demand is no longer for ideological purity or partisan loyalty, but for national dignity, collective strategy, and long-term vision.

The Middle East is changing with startling speed. States collapse overnight; new orders emerge just as quickly. When future openings appear, as they inevitably will, Kurdish regions must be prepared not only militarily, but politically and psychologically. That preparation begins with a shared national consciousness and leaders willing to listen rather than impose, to represent rather than bargain away fundamental rights.

Rojava’s suffering should not be romanticized. But neither should it be misunderstood. What looks like defeat today may, in time, be remembered as the moment Kurds fully grasped the cost of statelessness, and the necessity of overcoming it together.

History rarely grants liberation without first demanding clarity. Rojava has paid dearly for that clarity. The question now is whether the world is prepared for what a politically unified Kurdish nation may soon demand: full democratic rights, genuine autonomy, or, ultimately, a free Kurdistan.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Kurdistan24.