Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

Writer

Kurdistan Resumes Its Oil Export Amid Political Tensions

Kurdistan resumes oil exports after 30 months, signaling fragile progress in Baghdad–Erbil ties ahead of Iraq’s elections but raising doubts over lasting autonomy.

By: Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

On October 2, 2025, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq resumed its oil exports through the Ceyhan pipeline after a 30-month hiatus. This development marks a significant shift in Iraq's complex political landscape, characterised by historical disputes over resource control, federalism, and regional autonomy. The agreement, though a step toward economic stability for the Kurdistan Region, raises questions about the sustainability of such compromises in the face of Iraq's entrenched political challenges.

The deal brokered between Baghdad, Erbil, and international oil companies stipulates that the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) will transfer at least 230,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil to Iraq’s State Oil Marketing Organisation (SOMO), while retaining 50,000 bpd for local consumption. In exchange, the KRG will receive $16 per barrel to cover production and transportation costs. The agreement also includes provisions for resolving approximately $1 billion in arrears owed to oil companies operating in the region. While this arrangement provides immediate financial relief to the Kurdistan Region, it also signifies a shift in the balance of power. The KRG’s relinquishment of independent oil marketing rights and the integration of Kurdistan Region’s oil into the federal budget law represent a consolidation of Baghdad’s control over the country’s oil resources.

Elections….

The timing of this deal is politically charged. Iraq heads to legislative elections on 11 November 2025, and the oil compromise may well become a weapon in the hands of competing blocs. While attending the Chatham House Iraq Initiative 2025 conference in London last week, experts warned that voter apathy threatens to render the elections the least participatory since 2003. Polling suggests turnout may fall to 30–35% among Shia voters and 40–45% among Sunnis. Women, ironically, Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani’s strongest support base, are expected to participate in the lowest numbers. Of 29 million eligible Iraqis, only 21 million hold biometric voting cards, with boycott rates highest among Iraqis aged 35–45.

Despite this bleak outlook, Sudani currently enjoys the highest favourability ratings of any Iraqi prime minister since 2003. But popularity may not translate into power. As political scientist Renad Mansour of Chatham House highlighted, every election winner in Iraq has not formed a government. “The winner never wins anyway”. So, what’s the point of voting? Low turnout is likely to benefit entrenched figures like former PM Nouri al-Maliki, whose networks thrive on hollow electoral processes, while disadvantaging both Sudani and Parliament Speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi. This context fuels the Kurdistan Region’s anxieties. For two decades, Shia-led governments in Baghdad have often used post-election moments to roll back concessions granted to the Kurds in pre-election bargaining. Many in Erbil fear the October oil deal could meet the same fate.

Baghdad–Erbil Tensions….

The negotiation of the oil agreement was heavily shaped by U.S. pressure, with both Sudani and KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani personally invested in its success. But Sudani’s speech at the Chatham House conference unsettled KRG officials. By asserting that “all revenues, not just oil, should go to Baghdad,” he implied a centralisation of financial flows that goes far beyond the letter of the deal. For the Kurds, this rhetoric was a warning sign: oil agreements must remain distinct from other revenue streams if the KRG’s autonomy is to mean anything.

KRG politicians view such blurring as part of a broader trend. Since 2003, successive Baghdad governments have treated Erbil as a partner of necessity in fragile moments, only to sideline it once secure. The oil deal is thus less a breakthrough than another test of whether Iraq’s federal compact can function under sustained political pressure.

Kurdistan Voices…

At Chatham House, a senior KRG official sought to project optimism. Bayan Sami Abdulrahman, senior adviser to the KRG, described the agreement as “critically important” and a “win-win-win for all three parties,” noting that past disputes had cost Iraq as much as $25 billion in lost revenue.

Yet structural barriers persist. Kurdistan Region’s parliamentary seats remain capped regardless of voter turnout, disincentivising electoral participation and curbing Kurdistan’s influence nationally. Abdulrahman acknowledged this constraint but argued that the elections could provide an opportunity for a “reset” in relations. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the dominant force in Erbil, is banking on such a shift, though history gives little reason for confidence. Abdulrahman also stressed that the KRG remains anchored in the 2005 constitution, which she described as the glue holding Iraq together: “It gives something to every component in Iraq. At the end of the day, it’s the constitution that holds Iraq together. Here it is important to remember that Article 1 of the Iraqi constitution does not say that this constitution guarantees for Iraq its ones, but its unity, and unity means that this country encompasses several groups, and this should be respected, and Iraq should not be the tool of one group.

Iran’s Shadow….

No analysis of Iraqi politics can ignore the Iranian dimension. Tehran exerts significant sway over Baghdad through its support for Shia militias and political factions. This influence often tilts policy against Kurdistan’s interests. As deputy speaker of the Iraqi parliament, Shakhawan Abdullah charged recently, Baghdad’s delays in transferring public sector salaries to the KRG are not accidental but deliberate, “taking pleasure in their hardship.”

Sudani’s call at Chatham House for Kurdistan to be treated like “any other governorate, like Maysan,” reinforced these fears. For many Kurds, equating their constitutionally recognised region with ordinary provinces erodes their hard-won autonomy. The reality is stark: as of October, many Kurdistani civil servants had only received their July pay. The oil deal has not yet translated into tangible relief for families waiting months for income.

Geopolitically….

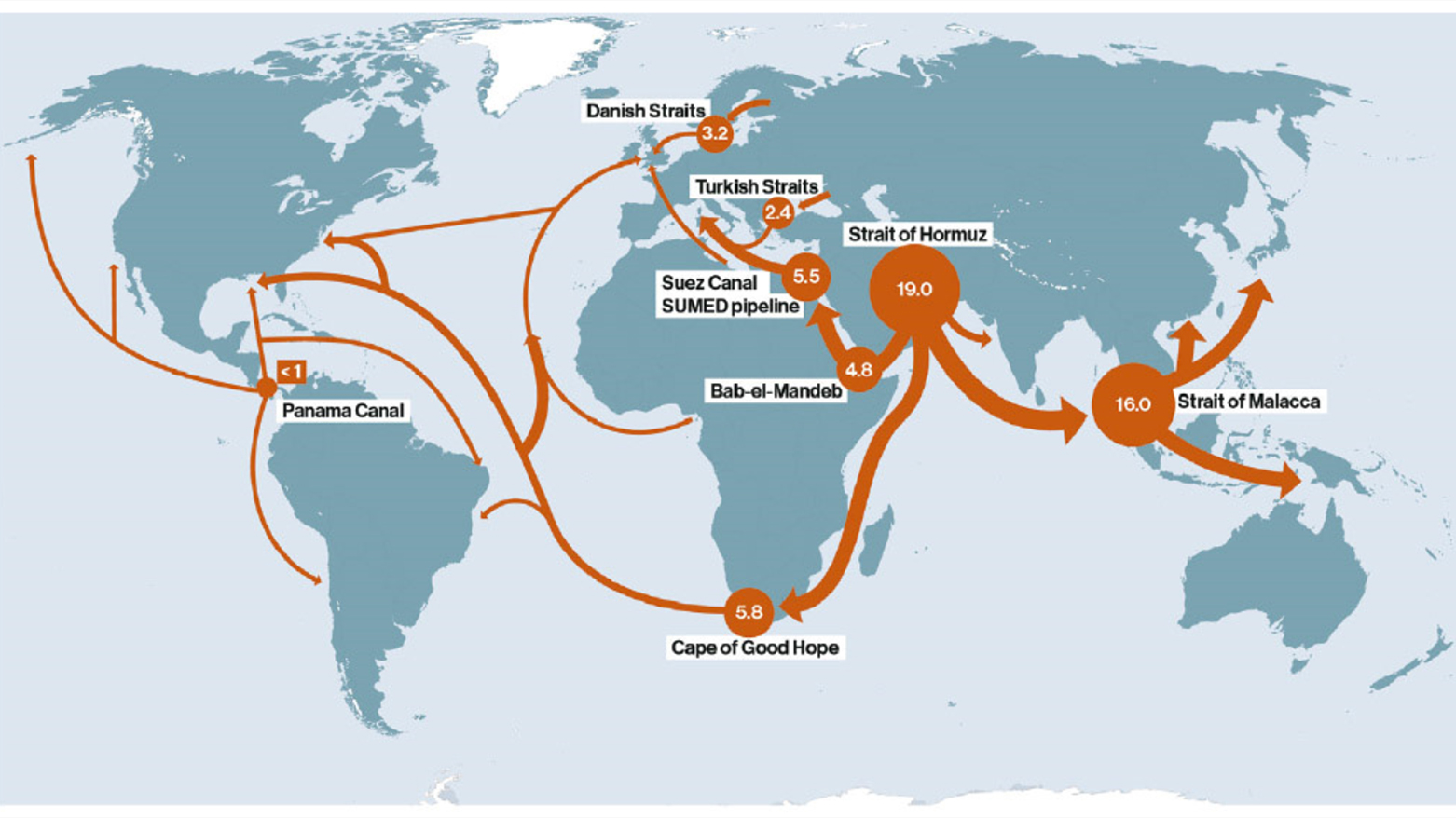

Beyond Iraq’s domestic struggles, the resumption of the Kurdistan Region’s oil exports has international significance. With the war in Ukraine disrupting Russian supplies, Europe is desperate for diversified energy sources. Kurdistan Region’s oil piped through Turkey to the Mediterranean represents a modest but symbolically important addition to Europe’s energy security. As Reuters recently noted, even incremental flows from Kurdistan can help stabilise volatile global oil markets.

For Turkey, the pipeline offers leverage over both Baghdad and Erbil, reinforcing Ankara’s position as a critical transit hub. Washington, meanwhile, has framed the deal as part of its strategy to stabilise Iraq while countering Iranian influence. Yet the U.S. faces its own dilemma: pressuring

Baghdad to respect for Kurdistan Region’s autonomy risks undermining its wider relationship with Sudani’s government, which Washington views as a rare point of relative stability in the region.

Federalism….

The current budgetary arrangement between Baghdad and Erbil is set to expire in December 2025. This looming deadline means that KRG public employees may once again face salary crises as negotiations over the 2026 budget begin. Without a permanent constitutional settlement on hydrocarbons and revenue-sharing, the cycle of disputes and temporary fixes will continue.

The deeper question is whether Iraq’s federal system can evolve into a genuine partnership. Can the constitution’s promise of power-sharing be realised, or will Baghdad continue to centralise under the cover of electoral politics? For the Kurds, the stakes are existential: without financial autonomy, political autonomy may soon prove hollow.

A Deal or a Mirage?

The October resumption of Kurdistan Region’s oil exports has been hailed as a breakthrough. It is a fragile compromise born of necessity, vulnerable to the political currents of Baghdad and the region. As Iraq heads into another election marked by apathy, manipulation, and the heavy hand of external powers, the durability of this deal remains uncertain.

For Europe, the United States, and Turkey, Kurdistan Region’s oil is a strategic asset. For Erbil, it is a lifeline. For Baghdad, it is a lever of control. Whether this triangle of interests can produce stability or merely delay another breakdown will determine not only the fate of Iraq’s fragile democracy but also the future of the Kurdistani people’s quest for dignity and self-determination.

Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

SOAS Global Development MSc candidate

London, United Kingdom

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Kurdistan24 English.