Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

Writer

Water Crisis: Climate Stress, Economic Pressures, and the New Politics of Survival

Analyst Ahmad Alkuchikmulla outlines how the Kurdistan Region is proactively responding to climate-driven water scarcity through infrastructure investment, data-driven governance, and international partnerships to build long-term resilience.

Water scarcity in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) is no longer a seasonal problem. It is increasingly shaping economic planning, agricultural sustainability, public services, and the region’s long-term political and security landscape. Climate projections in the 2024 Local Climate Change Adaptation Plan (LAP) reveal a concerning outlook: temperatures are projected to rise by between 1°C and 5°C across the Region’s governorates, annual rainfall is projected to continue declining, and days of extreme heat above 40°C are expected to triple, from around an average of 15–20 today to 50-60 days in Erbil, Sulaimani, Dohuk, and Halabja. The KRI’s climate is shifting at a pace that challenges existing institutional arrangements.

Climate Stress Meets Economic Reality

Across the region, climate pressures are intensifying simultaneously. Rainfall has become unpredictable, groundwater levels are dropping, and hotter summers are straining both irrigation networks and urban water systems. The LAP warns that drought cycles will deepen over the next decade, a trend already evident in agricultural areas around Garmian, Raperîn, and the Erbil plains, where crop failures and irrigation problems have accelerated the weakening of rural economic stability.

Urban areas face a parallel crisis. Erbil’s population growth and increasing household consumption have exerted significant pressure on municipal distribution systems. In response, the government has expanded well fields, replaced ageing pipelines, introduced digital metering systems, and rehabilitated parts of the urban network. These are important steps. However, as climate pressures intensify, stabilising supply is no longer just a technical challenge; it is becoming a fundamental aspect of economic planning, influencing industrial development, tourism forecasts, and investment decisions. The LAP makes this clear: water scarcity is no longer solely an environmental issue. It now directly intersects with service provision, job creation, infrastructure finance, and the broader economic reforms the KRG aims to promote. Water availability increasingly limits what development is possible and what can be sustained.

Governance Constraints and Regional Pressures

Climate change alone does not fully explain the severity of the challenge. Institutional arrangements also play a crucial role in shaping outcomes. The IRIS Water Policy Report (2017) highlights long-standing structural constraints: unregulated groundwater extraction, fragmented authority across agencies, weak coordination mechanisms, and gaps in hydrological data collection. These issues continue to limit the Region’s ability to convert climate assessments into coherent long-term planning.

None of these constraints reflects a lack of commitment; instead, they highlight the complexity of integrated climate governance worldwide and how challenging it has become. From southern Europe to Jordan, governments struggle to coordinate across agriculture, the environment, water, and municipal services. In the KRI, this fragmentation is evident in inconsistent enforcement of extraction rules, incomplete monitoring networks, and limited forecasting capacity that hampers the ability to anticipate shortages before they escalate into crises.

Layered on top of these internal constraints are geopolitical realities. The Kurdistan Region lies downstream of major river systems controlled by Turkey and Iran, whose dam construction and seasonal release decisions directly influence water entering Iraq. Unlike sovereign states, the KRG cannot negotiate transboundary agreements independently; it relies on Baghdad’s federal mechanisms. This structural asymmetry increases water insecurity and highlights why internal resilience, such as efficient usage, better regulation, and reliable data systems, is now one of the Region’s strongest tools for managing regional uncertainty.

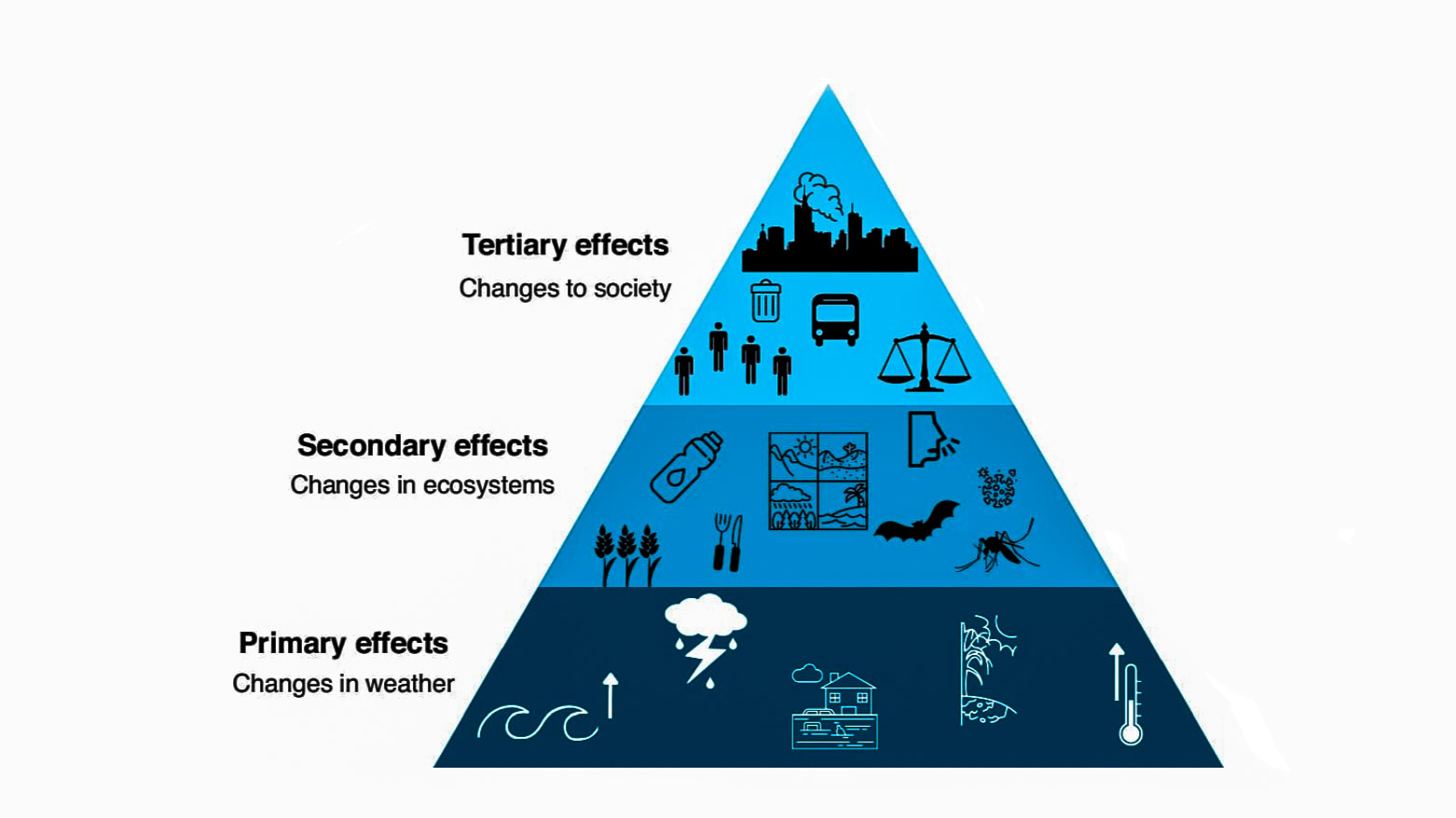

When climate pressures, institutional fragmentation, and upstream vulnerabilities converge, the result is a multi-dimensional challenge that now requires more coordinated and forward-looking approaches.

Communities on the Frontline and the Road Ahead

The first to suffer these pressures are rural communities. In villages across Erbil, Sulaimani, and the outskirts of Duhok, families face deepening wells, higher extraction costs, and declining harvests. Agriculture, once a stabilising economic force, is becoming more unpredictable. As rural livelihoods weaken, migration to cities increases, putting more strain on Erbil and Sulaimani’s already stretched water and service infrastructure.

Despite the scale of the problem, there are signs of movement. The KRG has launched modern irrigation pilots, invested in dam rehabilitation, expanded wastewater treatment for non-potable reuse, and collaborated with international partners to improve hydrological modelling and early warning systems. Erbil’s water directorate has begun implementing digital leak-detection technologies and pressure-management upgrades, offering early examples of how innovation can reduce losses and strengthen supply. In parallel, major infrastructure projects are underway, including a new rainwater drainage system along Erbil’s Kirkuk Road and a $424 million long-term water supply project linking Dukan Dam to Sulaimani, signalling a shift toward more resilient and future-focused urban water planning.

The challenge lies not in the lack of solutions, but in scaling them quickly enough. Pilot projects need to be expanded; data systems require consolidation; adaptation planning must incorporate climate projections rather than depend on historical data. Most importantly, water security must shift from a sectoral issue to a central pillar of economic, social, and security policy. Water scarcity in Kurdistan now poses a developmental challenge. It impacts household well-being, agricultural prospects, investment appeal, and political stability.

Recognizing this reality is the first step; building institutions capable of responding to it is the next. The Region’s leadership has signalled its awareness of these stakes, and the years ahead will determine whether Kurdistan transitions into a model of climate resilience or faces the increasing costs of slow adaptation.

The story of Kurdistan’s water crisis is ultimately a story of transformation. As the climate changes, old assumptions no longer hold. The decisions made now will shape the Region’s economic path, its ability to negotiate with neighbours, and its capacity to protect future generations.

Sources

Abdulrahman, S. (2020). Water Shortage in Iraq’s Kurdistan Region. Water International.

IRIS (Institute of Regional and International Studies). (2017). Water Resources Management in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Policy

Report.https://auis.edu.krd/iris/sites/default/files/Water%20Policy%20Report%20IRIS_FINAL%20ES.pdf.

Meihami, R. et al. (2025). Autonomy Within Sovereignty: The Multiscalar Hydropolitics of the Kurdistan Regional Government. World Water Policy.

UNDP & KRG (2024). Local Climate Change Adaptation Plan for the Kurdistan Region – Iraq. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-08/kurdistan_lap_-final_-_english.pdf.

Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

SOAS University of London Global Development MSc candidate

University of Bath, 1st Class BSc Politics with Economics Graduate.

London, United Kingdom

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Kurdistan24.