Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

Writer

Iraq’s 2025 Elections: Results, Realignments and Kurdistan’s Imperative

Analyst Ahmad Alkuchikmulla argues Iraq's 2025 elections show procedural democracy without meaningful reform, noting the KDP's 1+ million votes give Kurds leverage to demand constitutional implementation, Federal Council establishment, and revenue-sharing laws.

Iraq’s 2025 parliamentary elections unfolded at a critical moment, a test not only of political competition but of whether the state can renew trust through institutions rather than personalities. The outcome offers both continuity and potential recalibration, revealing how power is redistributed, how reform might still take root, and what the results mean for the Kurdistan Region’s place within a changing federal order.

On 11 November 2025, Iraq held its sixth parliamentary election since 2003, an exercise that should signal democratic consolidation. Instead, it revealed a deeper reality: the mechanisms of democracy persist, but meaningful political change remains stalled. Early returns from the Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) reveal entrenched blocs, subdued participation, and a public more resigned than represented (IHEC 2025; Al Jazeera 2025).

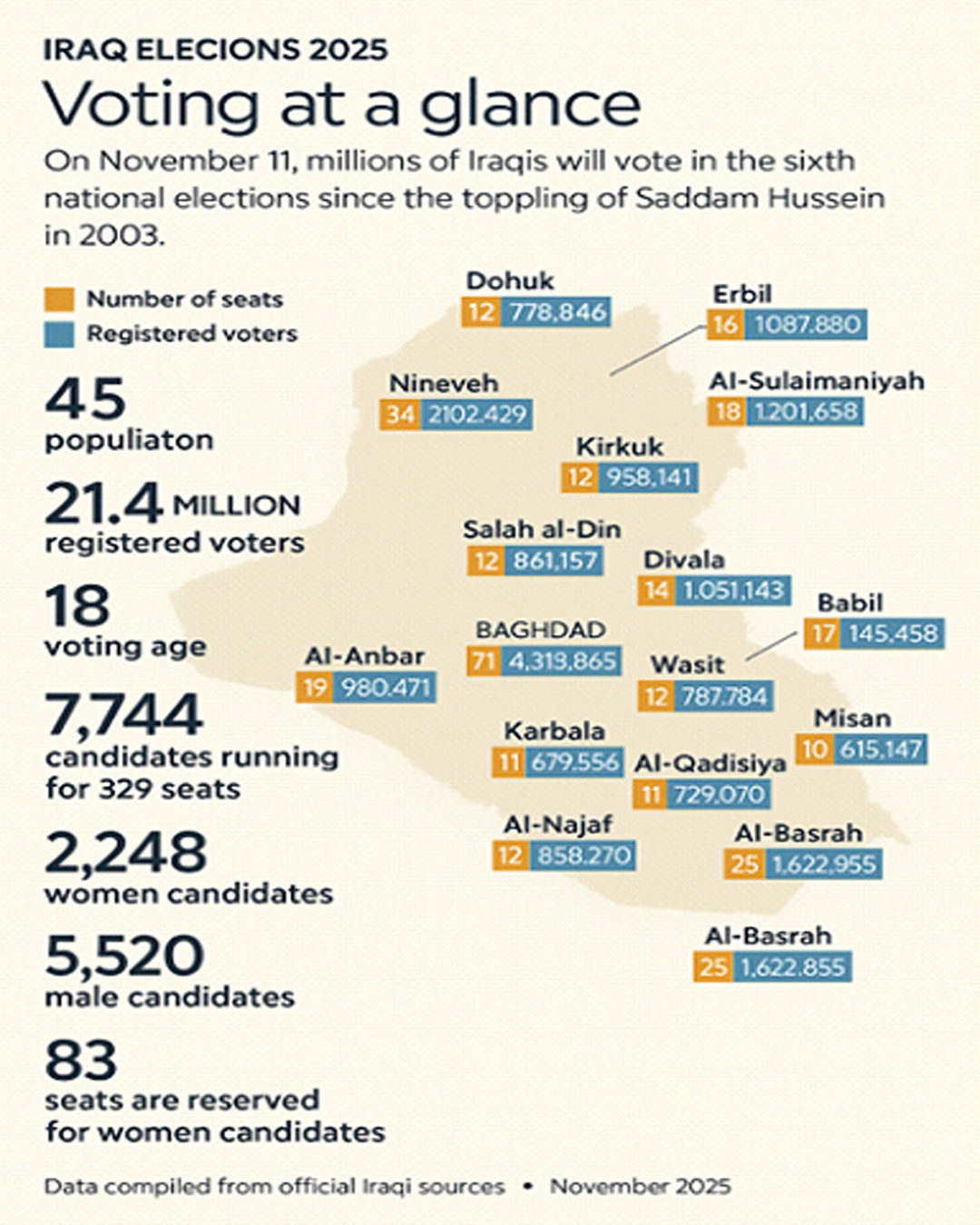

Iraq Elections 2025: Voting at a Glance

Note: Al-Basrah Governorate (25 seats, 1,622,855 registered voters) is not shown due to the map scale.

Credit: Adapted and redesigned by the author, based on publicly available electoral data (2025). Inspired by (Al Jazeera, 2025). Voting at a Glance presents key statistics for Iraq’s sixth national elections since 2003. The map of Iraq shows each governorate labelled with its number of parliamentary seats and registered voters. Major figures on the left note that Iraq has a population of 45 million, with 21.4 million registered voters, voting age of 18, and 7,744 candidates competing for 329 seats (including 2,248 women and 83 seats reserved for them). The design uses beige tones for seat numbers and blue tones for voter figures, with clear modern typography for accessibility.

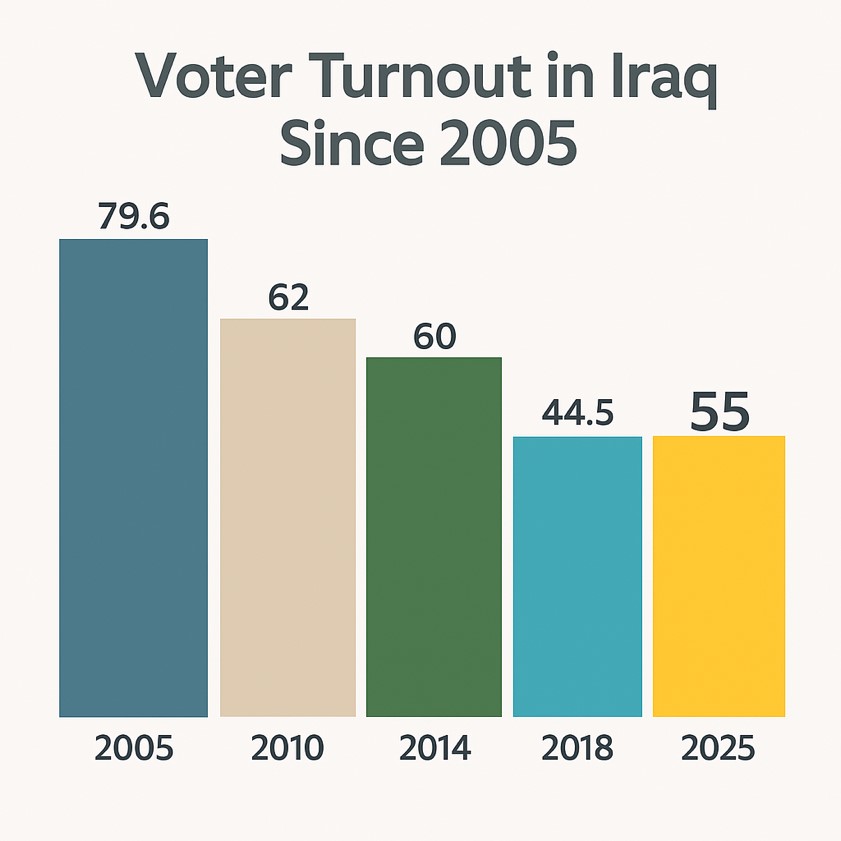

Voter Turnout in Iraq Since 2005

Note: Numbers presented are in percentages of voter Turnout in Iraq since 2005.

The IHEC announced voter turnout ‘exceeding 55 per cent’ of roughly 21 million registered voters, equivalent to 12 million ballots cast, though civil society monitors and independent observers dispute this methodology, noting that the Commission calculates participation only among updated registrants rather than all eligible citizens (IHEC, 2025; Al Jazeera, 2025).

Results and What They Reveal

No single party is expected to win the majority needed to form a government. Once preliminary results are announced, negotiations will begin among the leading blocs. The process is contentious and could stretch for months. Preliminary indications from Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) suggest that alliances aligned with Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al‑Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Coalition are set to emerge as the largest bloc with around 50-60 seats, with Nouri al‑Maliki’s State of Law coalition close behind with 30-40 seats. Taken together, Sunni-oriented coalitions, including Taqaddum, Al‑Siyada and Azm, are expected to secure a significant share of seats of 50-60. Although final tallies are yet to be confirmed, these trends point to a fragmented but familiar balance between established Shia parties and resurgent Sunni alliances, underscoring Iraq’s continued coalition-based political landscape. Notably, the Sadrist Movement, historically one of Iraq’s largest electoral forces, has boycotted this election. Its absence reshapes the parliamentary map, leaving the Shia field dominated by Sudani and Maliki’s blocs and altering the balance of bargaining power in post-election negotiations.

Major Political Blocs in the Iraqi Elections 2025

In the Kurdistan Region, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) again dominates, recording 1,099,826 votes, the second-highest votes for any single Iraqi party since 2005, while the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) follows with 548,296 (Kurdistan 24, 2025). Combined Kurdish representation, including smaller parties and minority quotas, is expected to approach 60 seats in the new Council of Representatives.

The IHEC reports turnout ‘exceeding 55 percent’ of 21 million registered voters, roughly 12 million ballots cast, though civil-society monitors dispute the method, noting that participation is measured among updated registrants rather than all eligible citizens (IHEC 2025; Al Jazeera 2025).

Yet numbers alone mislead. Elections in Iraq allocate bargaining chips, not authority. Power still flows through networks of loyalty, finance, and coercion. As Chatham House (2025) observes, “the real contest is not who wins votes, but how power is divided among the elites who dominate the system”. What stands out is the mismatch between votes and representation, for instance, the KDP, with more than one million votes, secured about 29 seats, while Sudani’s party just so far, with roughly 169,000 votes, secured 18 seats in Baghdad only. The distortion highlights how Iraq’s electoral formula rewards geographically concentrated blocs over parties with broad mandates. In Iraq, the arithmetic of power rarely matches the arithmetic of votes.

Kurdistan’s dimension

For the Kurdistan Region (KRI), participation is both imperative and a test. On election day, President Masoud Barzani described the KDP’s contestation as an act of constitutional commitment, grounded in the election triad hawbashi, hawsangi, sazan (partnership, balance, compatibility), signalling that Erbil continues to see its future inside a federal Iraq, provided Baghdad honours the bargain (Barzani, 2025).

Yet historical patterns are stark: each election brings pre-vote concessions to Kurdistan, only for post-vote centralisation to follow. Delayed salary transfers, budget gridlock and court rulings that weaken regional competencies all illustrate how Baghdad still wields fiscal and judicial levers of discipline (Reuters, 2025). The real question is whether the next cabinet will convert procedural legitimacy into constitutional responsibility.

Coalition arithmetic and Kurdish leverage

The emerging government will likely rest on a Shia Coordination Framework (SCF) core, a Sunni partner, and Kurdish endorsement to cross the 165-seat threshold. That gives KDP and PUK, with other KRI parties, a narrow but decisive margin of influence (Atlantic Council 2025).

1-To use it effectively, Kurdish parties must seek structural reform, not ministerial portfolios. Their joint agenda should be explicit and time-bound:

2-Constitute the Federal Council (Article 65): a bona fide second chamber with equal regional representation, replacing ad-hoc judicial intervention with institutional balance.

3-Pass a Hydrocarbons & Revenue-Sharing Law: automatic, audited monthly transfers to the KRG; local-consumption quotas ring-fenced; marketing revenues transparent; and force-majeure protection embedding salary payments beyond politics.

4-Implement Article 140 on a binding timetable: normalisation, census and referendum steps clearly defined to end legal limbo on disputed territories and restore trust.

5-Guarantee Security for the Region: explicit government-programme clause forbidding militia strikes on KRI territory; establish a Baghdad–Erbil permanent crisis management cell; security is not a concession but a constitutional obligation under Articles 117/121 (Constitution 2005).

6-Codify Peshmerga & Martyrs’ Rights: embed the Peshmerga in the federal defence architecture; dual command, budgetary clarity, and veteran/martyr recognition equal with federal armed forces (Constitution 2005; Reuters, 2025).

7-Reform the Electoral System: introduce a fair framework that prevents manipulation through turnout disparity.

Anything less risks reducing the Region to what Sudani once described as “just another governorate”. The Kurds should insist on co-operation, not absorption.

Inside the Kurdistan Region

Competition focused on Erbil (16 seats), Sulaimani (18) and Duhok (12), a majority of the KRI’s parliamentary presence. Preliminary data indicate that the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) remains the single largest party not only in the Region but in Iraq as a whole, the only political force since 2005 to secure more than one million votes as a single list (Kurdistan TV, 2025; Kurdistan 24, 2025). This reflects both its long-standing organisational discipline and the resonance of its developmental and federal vision.

The KDP is projected to win around 29 ± 1 seats, with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) 18 ± 1 seats, bringing overall Kurdish representation, including smaller movements and minority quotas, to roughly 60 ± 2 seats in the 329-member Council of Representatives (IHEC, 2025; Rudaw, 2025). The near parity between the two main Kurdish blocs underscores the need for post-electoral coordination, as Baghdad recognises that a divided Kurdish delegation weakens its collective bargaining power.

Following the vote, the KRG should act quickly to consolidate governance, finalise cabinet formation, and restore budgetary and administrative coherence across its institutions. The lesson is clear: Kurdistan’s influence in Baghdad begins with unity, competence, and stability at home.

Learning from the past, building for the future

Iraq’s structural malady is not merely corruption, it is architecture. With oil representing over 90 % of state revenues, ministries operate as factional fiefdoms, and public contracts serve as spoils. Elections merely repaint the machine. Without diversifying revenue, restructuring state entities and closing leakages in customs and fuel supply, the state remains a distribution network, not a developmental engine (Al Jazeera, 2025).

Two-thirds of Iraqis are under 30, with unemployment rates exceeding 15 % (Reuters, 2025). Governance itself has become a matter of national security.

Between geopolitics and governance

Externally, Iraq balances Iranian leverage, through armed factions, with Western scaffolding via financial and security cooperation. Sudani’s calls for a U.S. troop exit resonate domestically yet collide with Iraq’s reliance on Western credit and energy guarantees. For Kurdistan, this duality is starker. Oil exports revived in 2025 after a 30-month halt: both a lifeline and a liability. Unless the Baghdad–Erbil framework is legally codified and insulated from politics, the next crisis is one budget cycle away.

From sects to a state of law

Iraq’s political order will always reflect its three foundational communities, Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish, but democracy cannot survive as an arithmetic division. It requires constitutional conviction. The 2025 vote shows that procedure without reform is not progress.

If the incoming government uses its mandate to rebuild institutions rather than factions, by establishing the Federal Council, legislating a fair hydrocarbons and revenue-sharing law, sequencing Article 140, and addressing Iraq’s wider crises of justice, service delivery, and security governance, the country could finally begin a transition from survival to statehood. Reform must extend beyond Kurdistan’s fiscal question to encompass judicial independence, provincial empowerment, merit-based appointments, and a credible anti-corruption framework. Externally, Baghdad must balance regional alliances with a diplomacy anchored in sovereignty, not dependency.

If the next cabinet can unify these fronts, constitutional, economic, and geopolitical, Iraq may yet reclaim the promise of 2005. If not, 2025 will join 2018 and 2021 as another cycle of delay dressed as democracy.

Ahmad Alkuchikmulla

SOAS University of London Global Development MSc candidate

University of Bath, 1st Class BSc Politics with Economics Graduate.

London, United Kingdom

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Kurdistan24.