Dekan Cave Massacre: 56 Years On, Scars of a Brutal Attack Remain Etched in Stone and Memory

On the 56th anniversary of the Dekan Cave Massacre, families mourn the 75 Kurds, mostly women and children, killed by the Ba'ath regime in 1969. Survivors demand the rebuilding of their abandoned village, as the site remains an unhealed wound.

ERBIL (Kurdistan24) – On a day of somber remembrance, the soot-stained walls of a cave in Duhok province stand as a grim, silent testament to a crime that unfolded 56 years ago. For the families of the victims of the Dekan Cave Massacre, August 18 is not merely a date on the calendar but a day of profound grief, where the passage of more than half a century has done little to soothe the pain of an unimaginable loss.

It was on this day in 1969 that an Iraqi army offensive culminated in the martyrdom of dozens of innocent women, children, and elderly who had sought shelter from the violence, their sanctuary horrifically turned into a fiery tomb.

On the 56th anniversary of the massacre, descendants and relatives of the martyrs gathered to honor their memory, their sorrow as palpable as the day the horrors of the crime unfolded.

Newzad Dekani, a relative of one of the victims, conveyed the enduring weight of the event in a statement to Kurdistan24. "It is a heartbreaking tragedy, we hope it never happens to anyone," he said, his voice heavy with emotion. For him and others, the site is both a source of deep anguish and a place of pilgrimage. "We often visit this cemetery to soothe our grief and pain." The emotional toll remains so severe that upon entering the cave where his relatives were martyred en masse, Mr. Dekani finds himself unable to stand.

The physical reminders of the atrocity are stark and unsettling. To this day, soot from the fire that claimed so many lives clings to the cave walls, a permanent shadow of the horror.

In a deeply poignant and disturbing detail, the bones and remains of the martyrs have still not been collected from the site, leaving the cave as an open grave and a raw, unhealed wound.

Kamal Yaqub, who lost two brothers in the massacre, spoke of the motivation behind the attack with resolute clarity. "Our relatives were martyred only because they were Kurds," he told Kurdistan24. "There were 75 of them, and we are proud of them." His grief is now entwined with a demand for justice and restoration. "Our village has been abandoned for more than 50 years; we demand that it be rebuilt."

The saga of the Dekan Cave occurred within the broader context of a fierce conflict between Peshmerga forces and the Iraqi army.

The Baathist regime, having seized power in a military coup in July 1968, quickly reneged on its initial, baseless promises to resolve the Kurdish issue. By late 1968, attacks on Peshmerga positions had resumed, escalating into a major military campaign against the Akre-Shekhan region in mid-August 1969.

This offensive, supervised by then-Interior Minister Salih Mahdi Ammash and commanded by the head of the Fourth Division, Abdul-Jabbar al-Asadi, was designed to crush the September Revolution.

The village of Dekan, once a picturesque settlement of 20 to 30 families known for its vineyards and fruit gardens at the foot of Mount Khairi, found itself directly in the path of this military onslaught.

Supported by hundreds of hired mercenaries (or locally known as Jash) and heavy artillery, the Iraqi army descended upon the region, bombarding it from the air and ground. The local Peshmerga force, under the command of Taymur Abdal Shekhki, mounted a defense with the light weapons at their disposal.

As the assault intensified, the civilian population of Dekan, comprised mostly of women, children, and the elderly, sought refuge in a nearby cave to escape the indiscriminate shelling.

In an attempt to conceal their location, a large amount of twigs and wood had been gathered in front of the cave entrance. On August 18, 1969, advancing army units and their mercenary allies reached the village. After looting and setting fire to the villagers' homes, they began a search that led them to the cave.

What followed was an act of unspeakable brutality.

The soldiers and hired gunmen relentlessly showered the cave with bullets and set fire to the wood gathered at its mouth. The sounds of gunfire mingled with the groans and screams of the women and children trapped inside.

An elderly, infirm man was the first to be martyred, shot in front of the cave. Some women reportedly tried to leap through the flames towards a nearby stream, but they were so severely burned they could not reach the water and were martyred. Not a single person escaped. In the inferno of smoke, flames, and bullets, all were killed—a group reported to include 75 individuals, with detailed accounts confirming the deaths of 37 children, 29 women, and one elderly man.

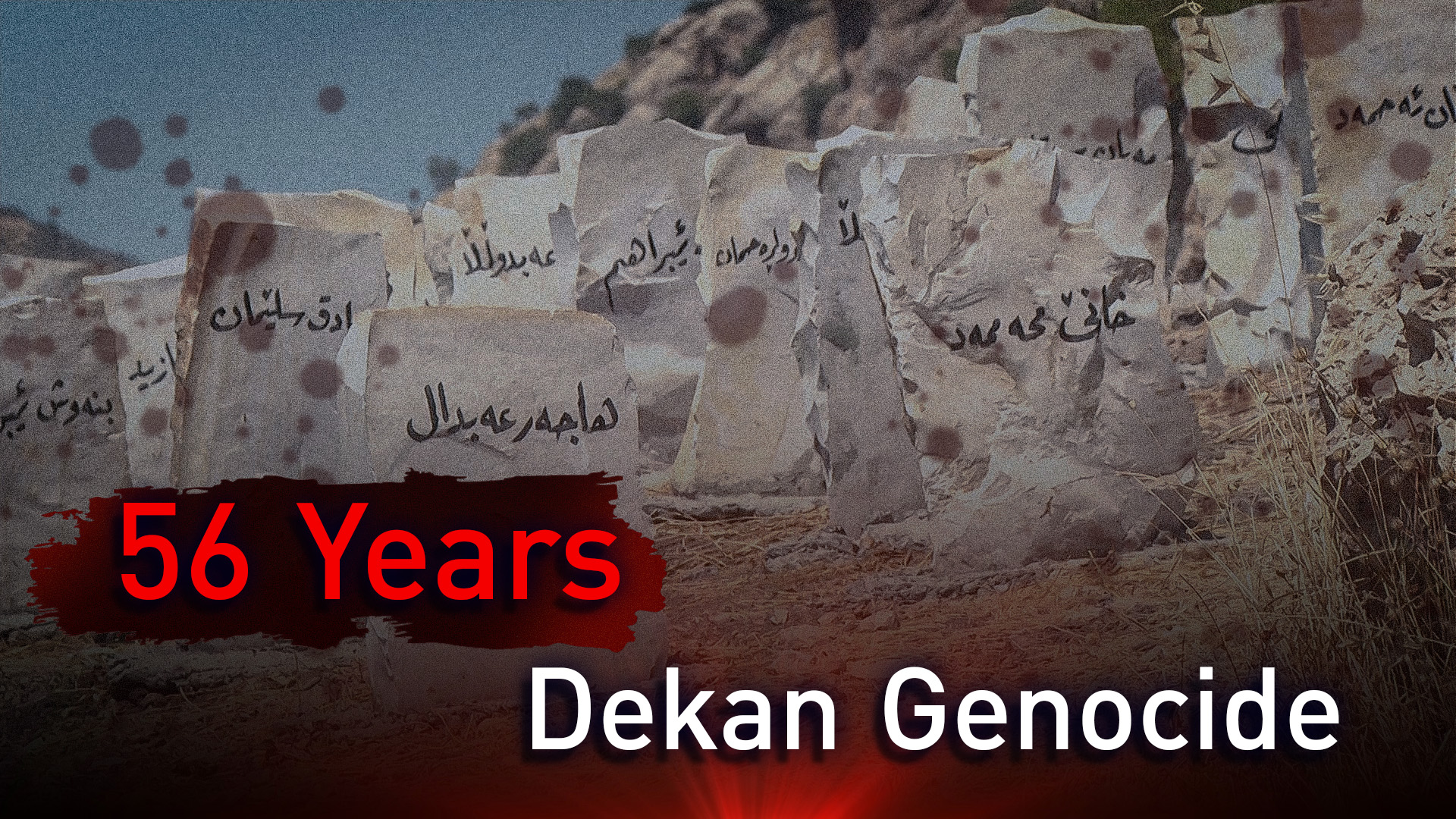

A few days later, a group of Peshmerga fighters who learned of the disaster made their way to the cave, only to find it was too late. With the help of people from the surrounding area, they established a cemetery near the cave and buried the victims.

The massacre triggered a retaliatory attack by Peshmerga forces on the villages of the Herki mercenaries, underscoring the brutal cycle of violence that defined the era.

Today, the abandoned village and the scarred cave remain a solemn monument to a day of immense suffering and a powerful call for remembrance and recognition.