After U.S. Strikes, Iran Increases Work at Mysterious Underground Site

Following U.S. and Israeli strikes on its nuclear facilities in June, Iran has increased construction at a mysterious, deeply buried underground site known as "Pickaxe Mountain," The Washington Post reported. The work suggests Tehran may be cautiously rebuilding and hardening its nuclear program.

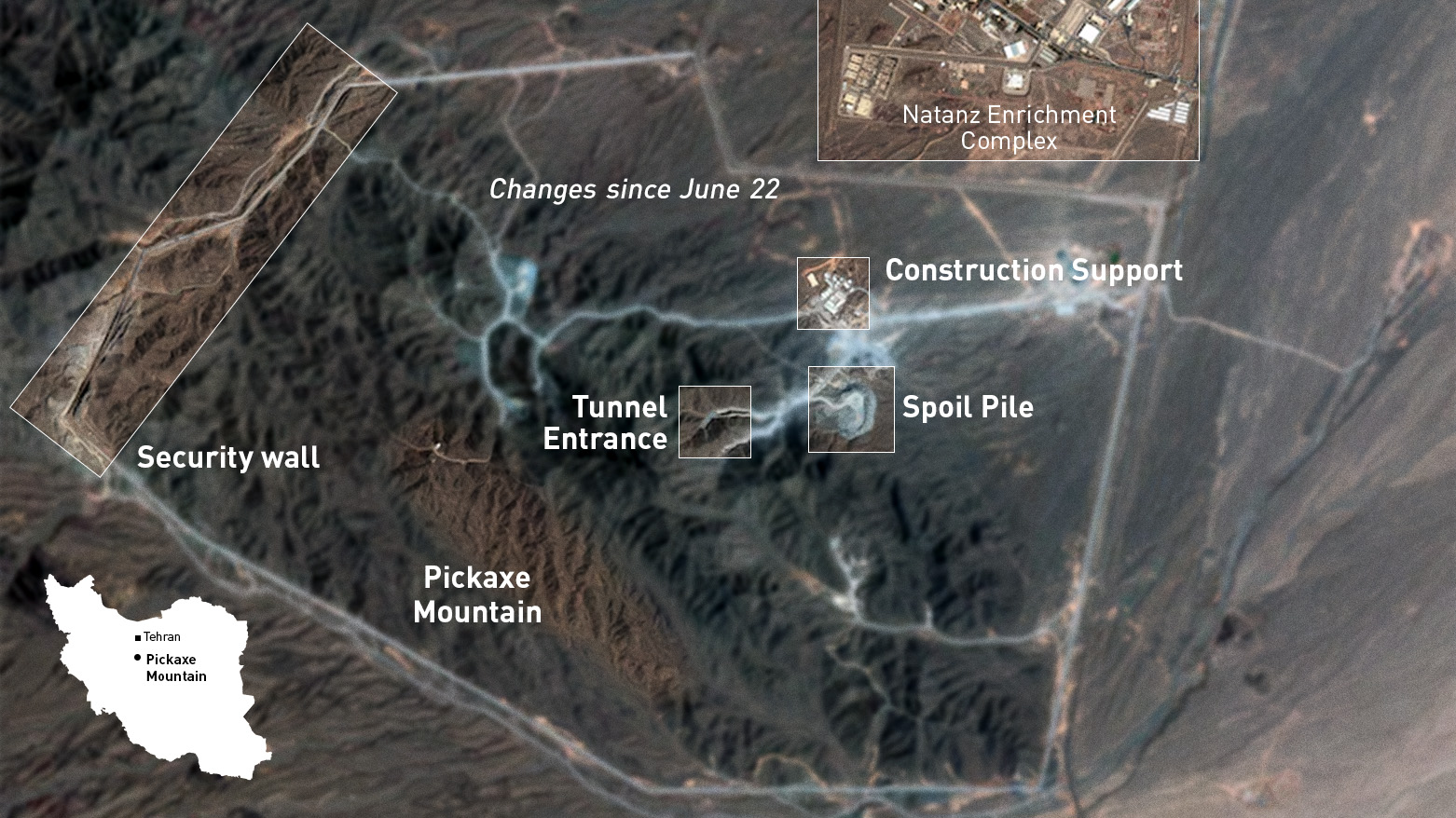

ERBIL (Kurdistan24) – In the wake of devastating U.S. and Israeli military strikes that pummeled its main nuclear facilities in June, Iran has accelerated construction at a mysterious and deeply buried underground complex, suggesting Tehran is cautiously moving to protect and potentially rebuild sensitive elements of its nuclear program. According to a comprehensive review of satellite imagery by The Washington Post, the increased activity is centered at a site known as Kuh-e Kolang Gaz La, or "Pickaxe Mountain," located just south of the Natanz nuclear complex, a primary target of the June bombardment.

The ongoing work at the heavily fortified mountain site, which has never been visited by international nuclear inspectors, raises significant questions about Iran's intentions as it navigates a precarious new reality. The Post's review, supported by analysis from independent experts, revealed three major changes at the facility since the U.S. strikes on June 22: the near-completion of a security perimeter, the reinforcement of a tunnel entrance, and a noticeable increase in excavated material, all of which point to continued and possibly expanded underground construction.

The purpose of the Pickaxe Mountain facility remains officially unconfirmed. When Iran first announced its plans for the site in 2020, it stated that the facility would house a new plant for assembling centrifuges, the fast-spinning machines used for enriching uranium.

This new plant was intended to replace a surface-level site at Natanz that was destroyed in what Tehran described as an act of sabotage. However, the sheer scale and depth of the new underground complex have fueled suspicions among analysts that its purpose may be far more sensitive.

Experts who have monitored its construction estimate that the halls being carved deep into the Zagros mountain range may be buried between 260 and 330 feet underground—potentially even deeper than Iran's Fordow facility, which was a key target of massive U.S. earth-penetrating bombs.

The Washington Post reported that this has led to speculation that the site could be intended as a new, covert uranium enrichment facility or a secure storage location for Iran's existing stockpiles of near-weapons-grade uranium.

Recent satellite imagery, as analyzed by experts at The Post's request, has captured the presence of heavy equipment and construction vehicles, indicating a deliberate and ongoing effort. "The presence of dump trucks, trailers, and other heavy equipment … indicates continued construction and expansion of the underground facility," Joseph Rodgers, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the newspaper.

The images show that a 4,000-foot section of a security wall has been erected since the end of June, bringing the full enclosure of the sprawling, one-square-mile site closer to completion. Furthermore, one of the eastern tunnel entrances has been covered with dirt and rock, a technique used to "harden it against airstrikes," according to Sarah Burkhard of the Institute for Science and International Security, which tracks nuclear proliferation.

The continued growth of the "spoil pile" of excavated earth and rock also provides clear evidence of ongoing tunneling. "The fact they’re continuing to build this is significant," Burkhard told The Post.

The increased activity at this hardened site comes after Iran's known nuclear infrastructure suffered severe damage. The Washington Post detailed how U.S. B-2 Spirit bombers dropped massive ground-penetrating bombs, known as Massive Ordnance Penetrators, on the uranium enrichment facilities at Fordow and Natanz, while Tomahawk missiles struck the Isfahan complex.

A September 8 report by the Institute for Science and International Security, based in part on data from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), concluded that the attacks had destroyed or rendered inoperable all of Iran's nearly 22,000 centrifuges. "For the first time in over 15 years, Iran has no identifiable route to produce weapon-grade uranium … in its centrifuge plants," the report stated.

While President Donald Trump claimed in the aftermath of the strikes that Tehran's nuclear capabilities were "totally obliterated," secret U.S. intelligence assessments have been less definitive. The Post reported that while assessments in July indicated the strikes had successfully collapsed the deeply buried infrastructure at Fordow, it was less clear whether Natanz and Isfahan had received similar knockout blows.

Analysts who spoke with the newspaper suggested that the limited new activity at these known sites, combined with the accelerated work at Pickaxe Mountain, indicates that Iran is wary of another round of airstrikes and may be shifting its strategy. "Post attack, Iran may have decided to enlarge the facility to move additional activities underground," Jeffrey Lewis, a nuclear expert at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, told The Post.

A critical and unresolved question is the fate of Iran's stockpile of highly enriched uranium. Before the June strikes, the IAEA had reported that Iran had accumulated nearly 900 pounds of uranium enriched to 60 percent purity—a short technical step from the 90 percent needed for a weapon. The location of this stockpile is now unknown. IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi told the "PBS NewsHour" on Monday that his agency believes the material is buried underground.

CIA Director John Ratcliffe, as reported by The Post, told lawmakers in June that U.S. spy agencies assess that most of this material is trapped under the rubble at Isfahan and Fordow. However, the uncertainty raises concerns that Iran could, over time, covertly use this material to produce the ingredients for a nuclear device.

Gauging Iran's next steps has been complicated by its mixed signals and lack of full cooperation with the IAEA. Although Tehran and the IAEA reached an agreement on September 9 for renewed access and reporting, Iran has since called that agreement into question amid the potential reimposition of international sanctions.

In an interview with PBS's "Frontline" program on Monday, Ali Larijani, the secretary of Iran's Supreme National Security Council, threatened that "we will end our participation with the IAEA" if sanctions are enforced. When asked about Pickaxe Mountain, he gave an ambiguous reply, stating, "We haven’t abandoned any of those locations. But in the future they could possibly continue to run as they currently do or be shut down." The final say on all nuclear matters rests with Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The White House, for its part, has made it clear that it is watching closely. "The administration will continue to monitor any attempt by Iran to rebuild its nuclear program. As President Trump has said, he will never allow Iran to obtain a nuclear weapon," a White House official told The Washington Post.

With Iran also reportedly rebuilding missile production sites targeted by Israel, according to the Associated Press, the accelerated construction deep inside Pickaxe Mountain serves as a clear and powerful signal that while Tehran's overt nuclear infrastructure may be in ruins, its ambitions, and potentially its capabilities, remain buried but very much alive.