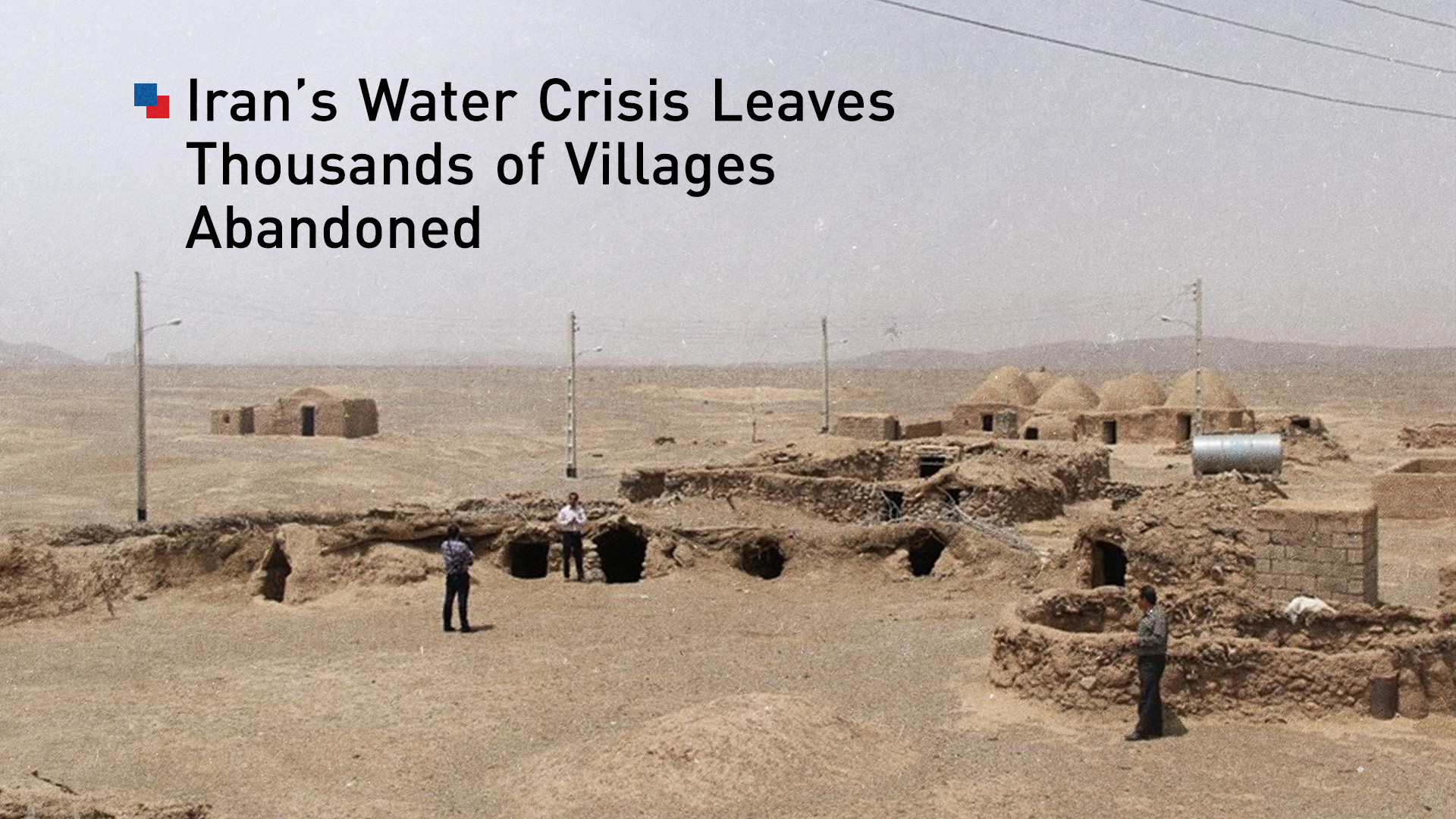

Drought and Water Mismanagement Leave Thousands of Iranian Villages Deserted

Iran faces a rural collapse with 31,000 villages deserted due to drought and water mismanagement. Officials report a massive demographic shift as drying wetlands force millions into cities.

ERBIL (Kurdistan24) — A deepening water crisis driven by persistent drought and systemic mismanagement of natural resources has precipitated a massive demographic shift across Iran, leaving tens of thousands of rural communities abandoned.

According to a report published on Tuesday by the state-affiliated IRNA news agency, the depletion of wetlands and vital water sources has rendered vast swathes of the countryside uninhabitable, forcing a migration of millions of residents into urban centers and creating a new class of environmental refugees.

The report, released on January 6, 2026, draws a direct correlation between the drying up of the nation’s critical wetlands and the collapse of rural viability.

The IRNA dispatch highlighted that thousands of villages have been deserted specifically due to the environmental degradation of their surroundings, with a significant concentration of these abandoned settlements located around the Salehiyeh and Hamoun wetlands.

The findings paint a picture of a nation where the traditional agrarian lifestyle is being systematically erased by a combination of climatological shifts and policy failures.

Abdolkarim Hosseinzadeh, Iran’s Vice President for Rural Development and Disadvantaged Areas, provided stark statistical evidence of the crisis.

In a statement cited by the news agency, Hosseinzadeh announced that out of the country's total of 69,000 villages, only 38,000 remain inhabited.

This leaves a staggering 31,000 villages—nearly 45 percent of the nation’s documented rural settlements—completely deserted. The figures underscore the scale of the displacement, suggesting that the rural backbone of the country is fracturing under the pressure of water scarcity.

Hosseinzadeh placed these current figures into a broader historical context, illustrating a complete inversion of Iran’s demographic structure over the past half-century. He emphasized that since 1976, the population distribution between villages and cities has reversed. Five decades ago, 70 percent of the Iranian population resided in villages, with only 30 percent living in urban areas.

Today, that ratio has flipped, a change Hosseinzadeh described as a "massive migration of rural residents." This rapid urbanization is not merely a result of industrialization but is being driven by the collapse of the rural resource base.

Ali Arvahi, an expert in wetland ecosystem management quoted in the report, detailed the mechanics of this collapse. He argued that the drying of wetlands does far more than remove a water source; it effectively severs the "livelihood chain" that sustains surrounding communities.

According to Arvahi, wetlands function as complex economic and environmental engines. They act as regulators of the regional climate, provide essential water for agriculture, serve as pastures for livestock, and act as a primary source for the fishing industry.

Beyond these economic functions, Arvahi noted that these bodies of water are considered an integral part of the community's cultural identity.

When a wetland disappears, the breakdown of the local economy is immediate and comprehensive. "When a wetland dries up, the agriculture surrounding that wetland is effectively destroyed as well," Arvahi stated. Without the ability to farm, graze animals, or fish, the economic rationale for the village’s existence dissolves, leaving residents with no option but to flee.

The expert provided a detailed list of the regions most acutely affected by this phenomenon. Citing field evidence and research conducted by ecosystem management teams, Arvahi pointed to specific environmental disasters that have triggered waves of migration.

He identified the Hoor al-Azim wetland, also known as the Great Marsh which straddles Iraq and Iran, in the oil-rich province of Khuzestan, Lake Urmia in the northwest, the Gavkhouni wetland in Isfahan, and the Bakhtegan and Tashk wetlands in Shiraz province as critical flashpoints.

Furthermore, he highlighted the Hamoun wetland in the southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan and the Miankaleh wetland, noting that at certain stages, the degradation of these sites has had the "greatest impact on the migration of their surrounding villages."

The pattern observed in these diverse geographic locations is identical: concurrent with the decline in wetland water levels, the villages bordering these ecosystems are emptied as their inhabitants migrate toward the cities.

The consequences of this forced relocation extend well beyond the physical movement of people.

Arvahi elaborated on the profound social and cultural ramifications of the crisis. He characterized the displaced populations as victims of "forced migration," a process that inflicts severe damage on the social fabric of the nation.

Among the primary impacts, he pointed to rising marginalization and poverty within the urban centers that receive these migrants.

The disintegration of social and familial ties is another casualty of this exodus. As villages empty, the local and regional cultures and traditions that were tied to the land and the specific water sources disappear.

Arvahi warned of the "loss of opportunities for social capital" in the abandoned areas, suggesting that the depopulation creates a vacuum where community cohesion once existed.

In the cities, the arrival of destitute rural populations often leads to an increase in social conflicts and a pervasive sense of marginalization among the newcomers.

Arvahi emphasized that forced migration creates a distinct "cultural conflict" between the traditional villagers and established city dwellers. This friction, he argued, becomes a source of significant social issues.

"In reality, these migrants generally do not have a good economic situation," Arvahi explained. The lack of financial resources and the struggle to adapt to urban economies can lead to an increase in social crimes.

The expert noted that this dynamic sometimes results in "another type of social and economic clash," as the pressures of urbanization collide with the desperation of those displaced by drought.

While the persistent drought is a primary driver of the crisis, the report makes clear that human error and policy decisions have exacerbated the situation. In his concluding remarks, Arvahi identified a series of management failures that have accelerated the drying of the wetlands and the subsequent destruction of agricultural lands.

He cited "poor management of water policy" as a critical factor. Specifically, Arvahi pointed to the "unplanned and excessive construction of dams" as a major intervention that has disrupted the natural flow of water to the wetlands.

Additionally, the "alteration of natural watercourses" and the "unregulated use of water for irrigating orchards" were identified as effective causes for the environmental collapse.

These policy missteps have had tangible results. Arvahi noted that the destructive impact of these decisions has become particularly evident in the areas surrounding Lake Urmia and the Bakhtegan wetland, where the diversion of water for upstream development has left downstream ecosystems—and the villages that rely on them—in ruins.

The IRNA report, supported by the data from the Vice President for Rural Development and the analysis from ecosystem experts, presents a grim outlook for Iran’s rural heartland.

With 31,000 villages already deserted and the water crisis showing no signs of abatement, the country faces a future defined by an increasingly urbanized population struggling to integrate millions of environmental refugees who have lost not only their livelihoods but their cultural heritage to the drying land.