“Ban Means Higher Prices”: Anger Erupts in Baghdad After Poultry Import Halt

Hundreds protest in Baghdad against Iraq's ban on frozen poultry imports, warning it will cause mass job losses and price hikes. Traders say local production can't meet demand, while the government claims the move supports farmers.

Erbil (Kurdistan24) – Hundreds of workers and traders staged a protest in Baghdad on Wednesday, voicing fierce opposition to the Iraqi cabinet’s recent decision to ban the import of frozen poultry. Demonstrators warned that the measure would strip thousands of their livelihoods, swell the ranks of the unemployed, and trigger steep price hikes that would burden ordinary citizens.

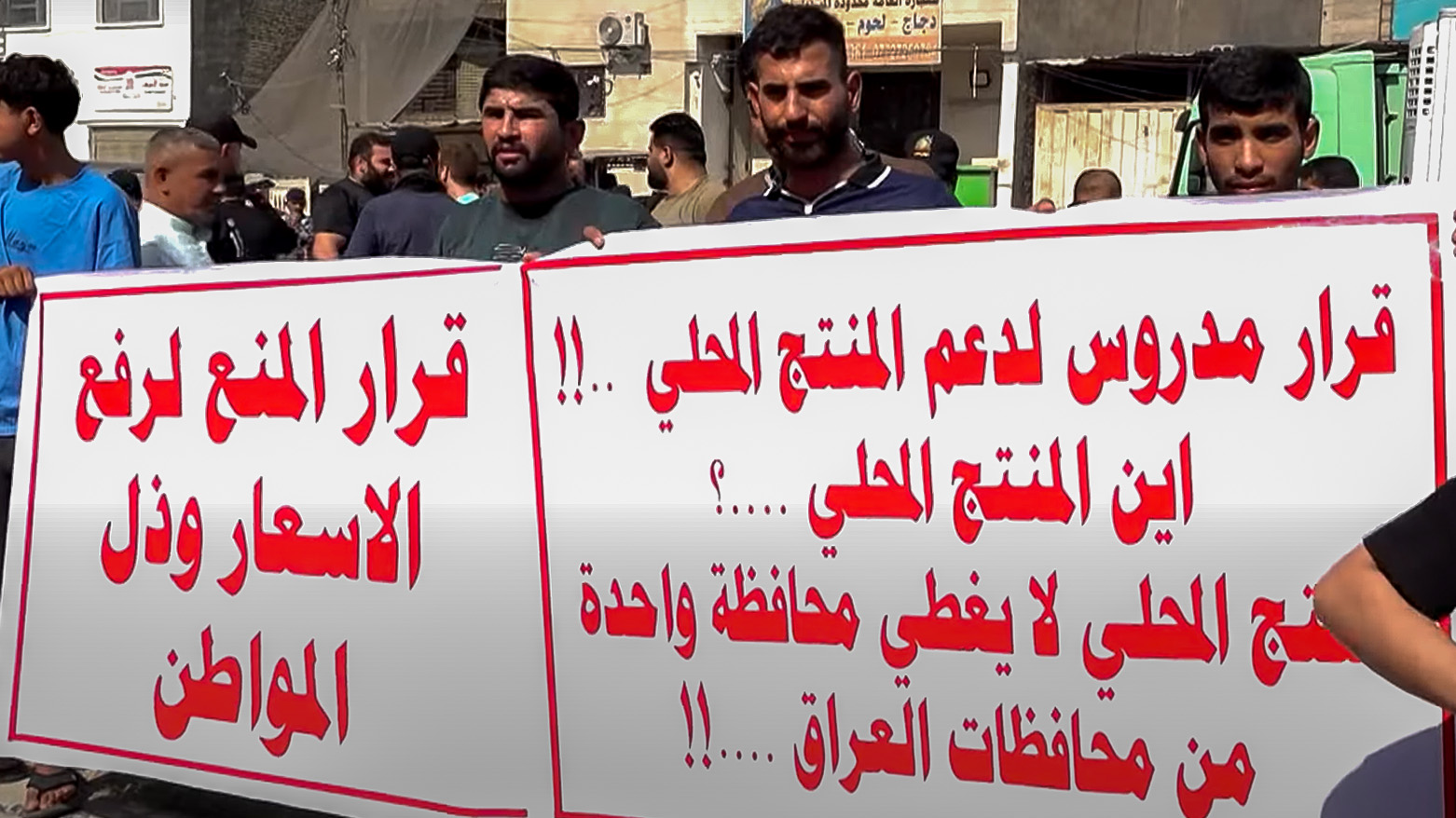

Carrying placards emblazoned with slogans such as “Ban Means Higher Prices” and “No to Market Monopoly,” the protesters issued a direct appeal to Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani to reconsider what they described as an “ill-conceived” decision that harms the most vulnerable segments of society.

One worker, speaking to Kurdistan24 under the looming threat of unemployment, expressed despair: “In each warehouse, hundreds of workers are employed. All of them are now without jobs. The entire Jamila commercial district has come to a halt. By God, we have no work left.”

Traders and warehouse owners stressed that the ban delivers a devastating blow both to their businesses and to consumers. “Halting imports harms us and it harms the people. Iraq is a consumer country, not a producer. This decision has stopped the work of companies and workers, and now our goods are spoiling,” one merchant told Kurdistan24.

Economists and importers argue that the cabinet’s measure undermines Iraq’s market stability rather than serving it, creating monopolies and violating international commitments. A prominent trader pointed out to Kurdistan24 that Iraq, as a member of the World Trade Organization, is bound by the principles of a free market.

He explained that the price of imported chicken currently stands at $2,000 per ton — roughly 3,000 dinars per kilogram — while the local product exceeds 5,000 dinars. “The biggest loser is the citizen,” he said, recalling a previous ban on egg imports that caused prices to soar from 32,000 dinars per carton to 70,000 dinars. He held Iraq’s economic council responsible for “poorly studied decisions” that damage both the economy and consumers.

With trucks laden with goods idling on the outskirts of the capital, traders anticipate a sharp rise in poultry prices in the coming days. Protesters insisted that domestic production cannot even meet the demand of a single province, let alone the needs of the entire country.

The Ministry of Agriculture defended the decision as part of a wider program to support the national economy. In a statement on September 17, ministry spokesman Mehdi Saher Jabouri announced a ban on the import of 44 agricultural and animal products, citing sufficient local production.

“The decision aims to stabilize prices for citizens and support local farmers and producers,” Jabouri declared, stressing the importance of tightening controls at border crossings to prevent smuggling and protect domestic output. He noted that Iraq relies on its annual agricultural calendar to adjust import policy: when local production is abundant, imports are blocked; when shortages arise, limited imports are permitted to meet consumer demand.

He added that customs duties imposed on many imported agricultural products are designed to secure the sale of local goods and protect farmers from losses.

Despite the government’s assurances, public anger continues to grow. For many Iraqis, the poultry ban symbolizes a broader disconnect between economic policy and the hardships facing the poor. With fears of soaring food prices, deepening unemployment, and mounting pressure on household incomes, protesters vowed to escalate their demands until the government reconsiders its decision.