‘No Food, No Doctors’: Kurdish Survivors Describe Libya’s Lawless Migrant Prisons

KRG repatriates 40 citizens detained in Libya. Survivors share harrowing tales of abuse, starvation, and official neglect on the perilous migration route.

ERBIL (Kurdistan24) – Forty citizens of the Kurdistan Region, their faces etched with a mixture of profound relief and the haunting memory of a harrowing ordeal, stepped onto the tarmac at Erbil International Airport on Sunday morning, their return marking the end of a perilous and often brutal journey that had led them into detention in the fractured state of Libya.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which arranged and funded their repatriation, announced their safe arrival, but it was the raw, unfiltered testimonies of the young men themselves that painted the most vivid picture of the "hard and difficult journey" they endured—a story of severe beatings, starvation, medical neglect, and the tragic death of a fellow migrant, all while trapped in a lawless land far from home.

In a statement released on Sunday, the KRG's Department of Media and Information confirmed that the 40 citizens had been arrested in Libya after attempting to reach Europe via illegal migration routes. Upon their arrival in Erbil, they were met by teams from the Ministry of Interior and the Department of Foreign Relations, as well as medical and assistance personnel.

The government confirmed that necessary medical examinations were performed to ensure their well-being before they were finally reunited with their anxious relatives.

However, the official statements of procedure could not fully capture the depth of the suffering described by the survivors. Their accounts peel back the layers of a desperate gamble gone wrong, revealing the stark human cost of the perilous Libyan migration route.

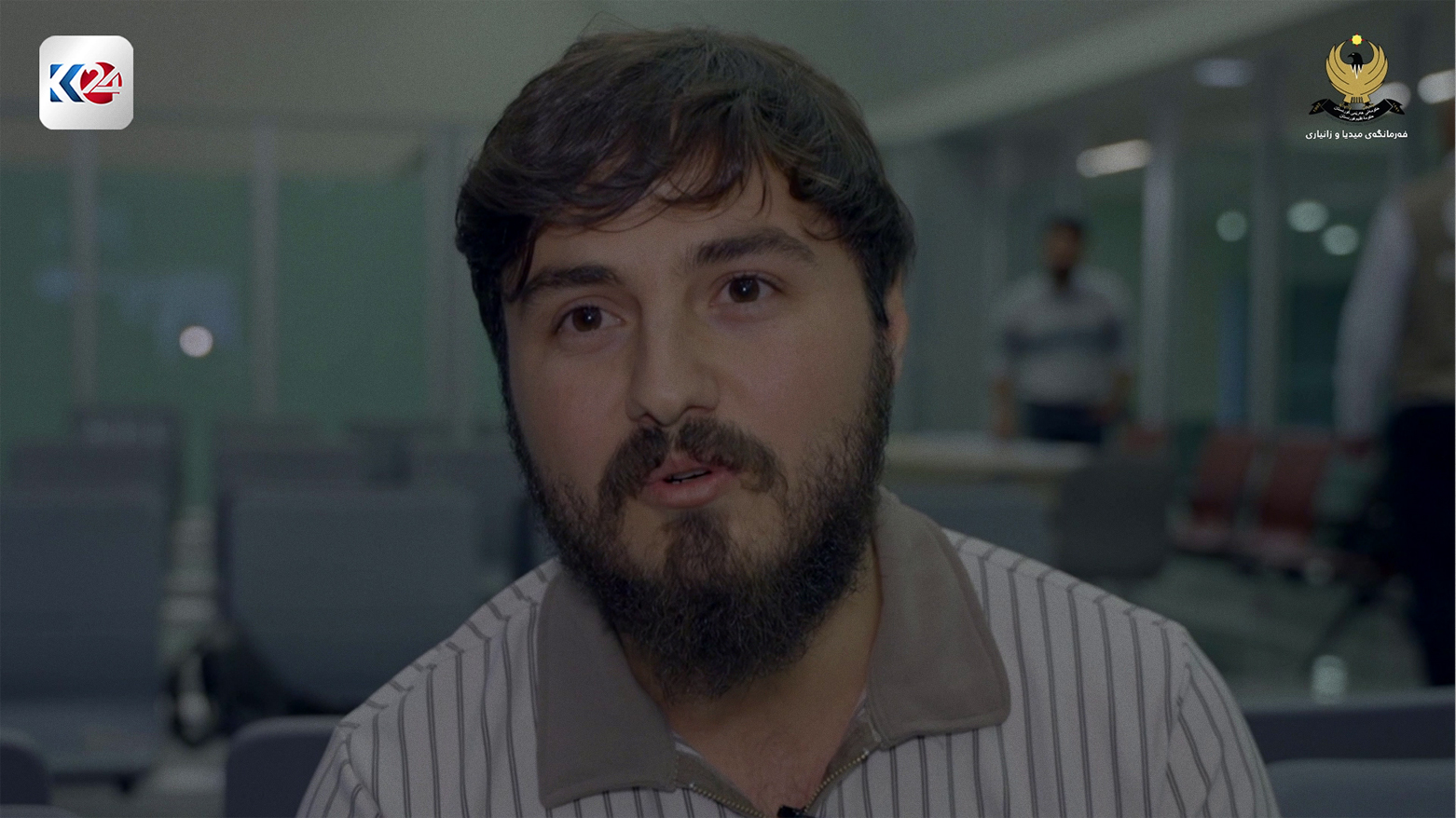

"They beat my friend so much, for absolutely nothing, without any reason," one of the repatriated citizens recounted, his voice heavy with the trauma of what he had witnessed. "I swear to God for three days his body was black and blue, I swear."

He expressed immense gratitude for the KRG's intervention, which he felt had come just in time. "We were detained there for forty days, in the camp... The Kurdistan Regional Government was very, very concerned about us, it came and helped us, truly it brought us back to Kurdistan. They helped us very, very much, may they be blessed, and we thank them.”

Another survivor spoke of a complete breakdown of human dignity and basic rights within the Libyan detention system. “We saw several hardships there. Over there, everything... I mean, there are no human rights, nothing at all," he said. "There is no food, our situation was bad, there was no medical care, there was nothing, nothing at all."

He credited the KRG's efforts for their safe return. "The Regional Government, I swear, as far as we knew, God willing we have returned safely, it did this work for us and our tickets were booked for us. Praise be to God, we arrived back safely. We thank those who worked hard for us.”

Perhaps the most chilling account came from a third young man, who detailed a prolonged period of near-starvation and the fatal consequences of medical neglect.

"We were detained for approximately fifty days. Truly, it's a catastrophe. Over there we had no life, we had no well-being, what can I say!" he lamented. "I mean, in terms of food and drink, we were at zero. We had one small loaf of bread a day."

The lack of medical attention proved deadly. "As for the rest, in terms of doctors, all of us had fallen ill, and no one would take us to a doctor, no one would check on us... Because the friend who was with us lost his life, that was 3 or 4 days ago. I mean, even if we were sick, they wouldn't take us to a doctor. Truly, they were very, very negligent.”

This survivor also drew a sharp contrast between the KRG's actions and what he perceived as inaction from federal authorities. "Thank God, the Regional Government came to our aid, they made a full effort for us... But the Iraqi embassy, truly the Iraqi ministry, nothing... it did not intervene in this matter, it did not help us at all.”

This latest repatriation is part of a sustained and coordinated effort to bring back citizens stranded in one of the world's most dangerous migration corridors. Just a day earlier, on Saturday, the Iraqi Embassy in Tripoli announced the successful repatriation of a separate group of 40 Kurdish migrants.

Forty citizens detained in Libya have been repatriated by the Kurdistan Regional Government, returning home after months of hardship. Their testimonies reveal the harrowing journey they endured before reaching safety.

— Kurdistan 24 English (@K24English) October 26, 2025

🔗: https://t.co/ZGsqFeebJe pic.twitter.com/dF7FyJOo5O

Speaking to Kurdistan24, Ahmad al-Sahhaf, the Iraqi chargé d’affaires in Libya, praised the "exceptional coordination" with the KRG and Libyan authorities in that operation and revealed that the embassy was preparing to repatriate an additional 35 migrants in the coming weeks. “We provided food, medicine, and care for our citizens and secured their travel tickets in coordination with the Kurdistan Regional Government,” said al-Sahhaf, noting that the embassy has returned a total of 122 Iraqi migrants since reopening.

His account of close cooperation stands in contrast to the criticism leveled by the migrant who returned on Sunday, highlighting the complex and sometimes contradictory perspectives on the ground.

These efforts are not new. On September 10, the KRG announced the return of 25 other Kurdish youths who had been detained in Libya for over fifty days. The consistent pattern of repatriations underscores the grim reality that a growing number of people from the Kurdistan Region and Iraq are risking everything on the Libyan route, a path paved with desperation.

Libya’s role as a critical transit hub for migrants is a direct consequence of its geography and its chaos. Its long Mediterranean coastline offers the shortest, albeit most treacherous, sea crossing to Italy. The power vacuum that followed the 2011 ouster of Muammar Gaddafi allowed a deeply entrenched network of human smugglers and traffickers to flourish, operating with near impunity in a lawless environment.

This brutal reality is fueled by powerful "push" factors, as migrants flee war, persecution, and extreme poverty, and the alluring "pull" of a more stable and prosperous future in Europe.

The journey itself is a litany of horrors. Long before reaching the coast, migrants must survive a perilous crossing of the Sahara Desert, where many succumb to starvation and dehydration. Those who survive often fall prey to kidnapping for ransom, forced labor, torture, and sexual violence.

The Global Detention Project has documented persistent and severe abuses across Libya’s network of detention centers, many controlled by militias, where overcrowding, starvation, and physical abuse are rampant. These documented conditions directly corroborate the harrowing testimonies of the young men who returned to Erbil.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and UNHCR, Libya hosted approximately 705,746 migrants as of April 2024. While most are from sub-Saharan Africa, a growing number of Iraqis and Syrians see the country as a gateway to Europe. Trafficking networks in eastern Libya are known to operate openly, holding migrants in makeshift warehouses and subjecting them to extortion and beatings until their families pay large ransoms.

While desperation fuels the migrants' journey, a complex and cynical political economy, heavily influenced by European policy, has turned their suffering into a lucrative industry, as detailed in a recent investigation by the French publication Le Monde diplomatique. The report, titled "The extortion state: how the EU helps Libya to turn migrants into cash," argues that the European Union’s push to curb Mediterranean crossings did not create Libya's extortion economy but has "supercharged it," making migrants pawns in a high-stakes game between the country’s rival governments and the powerful militias that control them.

The investigation highlights how European policies, primarily those focused on "externalisation"—paying non-European states to block migrant flows—have inadvertently shaped and incentivized the very systems of abuse that migrants face.

The report details the story of "Jackson," a young man from Cameroon, whose experience mirrors that of countless others. Intercepted by the EU-backed Libyan Coast Guard (LCG), he was taken not to an official facility, but to a series of underground pens and eventually a derelict factory known as the Al-Maya detention center. There, with over 1,000 others, he was held in a nearly hermetically sealed room where food and water were lowered by rope. His captors were blunt about their motives. When detainees asked to phone relatives for ransom money, a commander reportedly told them: "This place isn’t like other prisons. We don’t need your miserable money. We’re after the European Union. You can’t give us the sort of ransom the EU can."

This anecdote, as reported by Le Monde diplomatique, reveals a chilling evolution in the business model of Libyan militias. The Al-Maya scheme was orchestrated by the powerful Buzriba brothers, key figures in the local coastguard and the new Stability Support Apparatus (SSA).

Their goal was not just to extort money from migrants' families but to leverage their control over thousands of detainees to attract official recognition and funding from the EU and UN, which were already providing equipment and support to other Libyan bodies like the Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM). In effect, preventing migration became a more attractive business than facilitating it, as it offered official status, salaries, access to state budgets, and crucially, a direct line to international actors.

The report meticulously traces how this dynamic has led to the "conquest of the state by militia leaders." Figures who once ran notoriously abusive detention centers, such as Mohammed al-Khoja of Tariq al-Sikka and Emad Trabelsi of Al-Mabani, have ascended to the highest echelons of power, becoming the head of the DCIM and the Interior Minister, respectively.

Essam Buzriba is now the interior minister in Libya's parallel eastern government. As Le Monde diplomatique bluntly states, "Libya’s militias have become the state." This institutionalization of the extortion business means that the Libyan state itself now has deeply vested interests in the continuation of a system that thrives on the capture and detention of migrants—a system primarily supplied by the EU-supported interceptions of the Libyan Coast Guard.

This has empowered Libyan leaders to not only ransom individual migrants but to effectively extort European governments. The report details how Khalifa Haftar, who controls eastern Libya, demonstrated his ability to "turn the tap" of migration on and off.

In 2022, thousands of migrants suddenly began arriving in Italy from eastern Libya. After a panicked Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni received Haftar in Rome in May 2023, the boats stopped. The Haftars have since used this leverage to extract further concessions, training, and legitimacy from Italy and Greece, proving that they can weaponize migration flows to achieve their political aims.

This cynical game is further complicated by domestic Libyan politics, where widespread xenophobia is manipulated by political factions. The report describes a social media campaign that spread in March, accusing the Tripoli government of colluding with Italy in a "sinister plan to permanently settle migrants in Libya."

In response, the government panicked, ordering haphazard roundups of migrants and cracking down on international NGOs, accusing them of being part of a secret EU plot. This highlights the deep-seated suspicion and contradictory discourse within Libya, where migrants are simultaneously seen as a threat to be expelled and a valuable commodity to be controlled for financial and political gain.

Against this dark and complex backdrop, the repatriation efforts by the KRG and Iraq's diplomatic missions serve as a crucial, if limited, lifeline. Ahmad al-Sahhaf’s assertion that "Iraq has great potential in its youth sector and should no longer be a country of emigration" speaks to the ultimate solution: addressing the root causes that drive young people to undertake such a desperate journey in the first place.

For the 40 young men who landed in Erbil on Sunday, their journey home is the end of an unimaginable nightmare. Their stories, however, are a stark and urgent reminder of the profound desperation that continues to fuel the deadly exodus through Libya, and of the deeply compromised international system that has, in its effort to build a fortress, instead funded the dungeons.