Half a Century After Franco, Spain Still Digs for Truth—A Pain the Kurds Know Well

Fifty years after Franco's death, Spain grapples with his legacy as families race to exhume mass graves, a painful quest deeply understood by the Kurds.

ERBIL (Kurdistan24) – Half a century after the death of the dictator General Francisco Franco, a painful and enduring legacy of his brutal regime continues to scar the Spanish landscape, as a generation of aging sons and daughters races against the inexorable march of time in a desperate final quest to reclaim their dead.

For 88-year-old Maria Jesus Ezquerra, this race is deeply personal. Her only remaining dream is to recover the remains of her father, a Socialist councillor executed at the start of Spain's 1936-1939 civil war and dumped in a mass grave, so she can finally lay him to rest beside the mother he was forced to leave behind.

"It's my only dream, after that, I can die," she told Agence France-Presse, her words punctuated by tears streaming down her face.

"I have always loved my father very much, even without knowing him," she added, her voice choked with the sobs of a lifetime of loss, speaking from her home in the small village of Pinsoro in the northeastern region of Aragon.

Her story, as detailed in a poignant report by AFP, is a window into a national trauma that has remained just beneath the surface for decades.

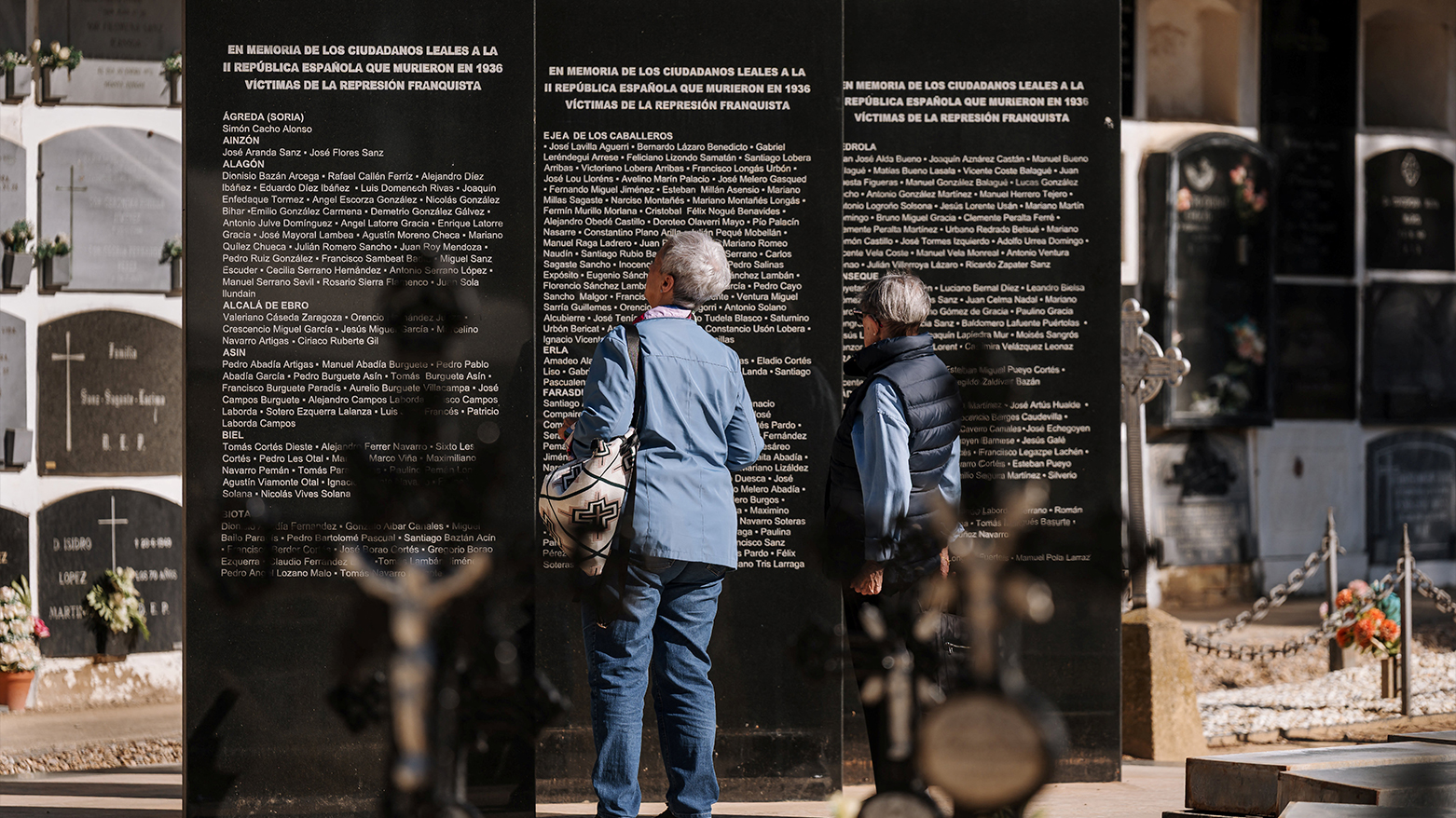

Her father, Jesus Ezquerra, a 38-year-old labourer, was arrested shortly after Franco's nationalist military coup in 1936 ignited the bloody civil war. He was a man of principle who, despite the clear and present danger of reprisals from the rightist forces, was unwilling to flee and abandon his wife—who was pregnant with Maria Jesus at the time—and their four other children. Two days after his arrest, he was buried in a common grave in the cemetery of the nearby town of Ejea de los Caballeros, one of an estimated 150 victims interred in that single, unmarked plot.

Now, 88 years later, a painstaking exhumation effort has finally begun at the Ejea cemetery.

For Maria Jesus, the opening of this grave represents the last, fleeting hope of fulfilling her lifelong dream. As one of the few surviving direct children of the victims buried there, her DNA provides the strongest possible chance of identifying her father's remains, a crucial key to unlocking the secrets of the past and providing a measure of closure for a wound that has never healed.

A Shared Pain Across Continents: The Kurdish Connection

The heart-wrenching quest of families in Spain to unearth the victims of a fascist regime resonates with a profound and painful familiarity for the people of Kurdistan, a nation that has endured its own century of systematic persecution, mass extermination, and the horror of countless undiscovered mass graves.

For the Kurds, the images of skeletal remains being carefully brushed clean in the soil of Aragon are not a distant historical echo but a visceral and contemporary reality, a shared experience of confronting the physical evidence of a genocidal mentality that seeks to erase a people from the earth.

The struggle in Spain to achieve historical justice, provide dignified burials, and ensure that such atrocities are never repeated is a struggle that the Kurdish people know all too well, having been on the receiving end of the same calculated brutality from the former Ba'athist regime in Iraq.

Just last week, as reported by Kurdistan24, President Masoud Barzani addressed the Fifth International Conference on the Recognition of the Kurdish Genocide, where he meticulously chronicled the systematic campaigns of annihilation waged against his people.

He spoke of the Anfal campaign, which saw over 182,000 Kurds murdered, many of them buried alive in the deserts of southern Iraq. He spoke of the chemical bombardment of Halabja, where suckling infants and pregnant mothers were gassed in the streets, and of the genocide against the Yazidis in 2014.

"The fate of the people of Kurdistan, throughout history, has been nothing but pain, suffering, and oppression," President Barzani stated, a sentiment that would find a sad echo in the living rooms of families in Pinsoro.

The parallels are haunting. While Spain contends with an estimated 140,000 missing persons from its civil war, the Kurds are still searching for the remains of tens of thousands of victims.

As recently as last month, Dhiaa Karim, Director General of Iraq’s Mass Graves Affairs and Protection Department, told Kurdistan24 that while 81 of 98 confirmed mass graves from the Ba'ath era have been excavated, the search continues, as the number of known graves is still far less than the number of recorded victims.

President Barzani's solemn vow at the conference—"until our last breath, we will try, so that not a single bone of our martyrs remains un-returned"—is the very same promise that fuels the aging children of Franco's victims in Spain.

The scientific and emotional challenges are also strikingly similar.

The AFP report from Spain highlights the difficulty of DNA identification, with the lack of a national genetic database and the death of most direct relatives making it nearly impossible to identify the vast majority of exhumed remains.

In Kurdistan, this challenge is being met with a concerted, state-sponsored scientific effort. At the Duhok conference, Professor Dr. Yassin Karim revealed the chilling power of modern forensics, announcing that scientific evidence had proven that at least 45 children were killed while still in their mothers' wombs during the Anfal campaign.

This new, scientifically grounded approach, as reported by Kurdistan24, is part of a strategic pivot to build an unassailable case for global recognition and justice, a path that Spanish activists are also treading.

A Landscape Scarred by Unmarked Graves

As Spain prepares to mark the 50th anniversary of Franco's death on November 20, 1975, the nation is being forced to confront the sheer scale of the historical injustice that his regime perpetrated. The Socialist government of Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez estimates that there are over 3,300 mass graves from the civil war.

The largest of these graves is located at an imposing monument near Madrid, once known as The Valley of the Fallen, where some 33,000 bodies from both sides of the conflict were interred, many of them Republicans moved there without their families' consent.

Franco himself was buried at the site until 2019, when the government exhumed his remains and relocated them to a more discreet family vault, a hugely symbolic act in the ongoing battle over the nation's historical memory.

A landmark "Democratic Memory Law" passed in 2022 finally made the Spanish state officially responsible for the exhumations. However, as the AFP report highlights, much of the difficult, on-the-ground work continues to be carried out by civil society organizations like the Asociacion Memoria Historica Batallon Cinco Villas, which is leading the search at the Ejea cemetery.

The process is painstakingly slow.

"We expect the project to last around two years because it requires significant resources," Javier Sumelzo, the 42-year-old secretary of the association, told AFP. Javier Ruiz, the 56-year-old archaeologist leading the excavation, explained that time is the greatest enemy, especially with the challenge of DNA identification.

"The worst part is opening a grave and being unable to identify almost anyone," he said.

Closing Wounds, Not Reopening Them

For the families who have waited a lifetime for this moment, the process, however painful, is a necessary step towards healing. This sentiment is a universal truth understood by survivors of state-sponsored terror everywhere.

Conchita Garcia, Maria Jesus's daughter, who has spent years campaigning for the exhumation of her grandfather's remains, pushes back against the argument that this work reopens old wounds. "These exhumations do not reopen wounds, they close them," she stated emphatically to AFP.

This is the very essence of the Kurdish demand for justice. As Prime Minister Masrour Barzani stated on the 37th anniversary of the Anfal campaign, the goal is to provide "just compensation—both material and moral" to the families of the victims.

For both the Spanish and the Kurds, this is not about revenge. President Masoud Barzani, in his conference speech, powerfully recounted how the Kurdish people, after the 1991 uprising, captured two full corps of the Iraqi army—the very soldiers who had carried out the Anfal—and yet, "not a single Iraqi soldier was killed, not a single one was humiliated."

The Kurds, he explained, chose forgiveness over revenge, a profound act of mercy that he lamented has yet to be fully appreciated by the world.

The ultimate goal, for both peoples, is to ensure such horrors are never repeated. For the families in Spain, like the three cousins who recently reburied their grandfather alongside his wife, the recovery of remains is, as they told AFP, "a relief, because you have found someone you never knew, but whom you loved."

It is this same sense of relief, of finding a loved one and closing a painful chapter, that continues to drive the 88-year-old Maria Jesus Ezquerra as she waits, hoping that her only dream will finally be fulfilled, a dream that is deeply and tragically understood in the mountains and valleys of Kurdistan.